Program At-A-Glance

Organizations: Health Plan of San Mateo and Inland Empire Health

Goal: Support individuals with long-term service and support needs who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid to live in their communities.

Key Elements: (1) Locating eligible individuals; (2) managing transitions, including finding the actual housing and planning for all service needs; and (3) providing post-transition services, including intensive care management, tenancy support, and other services, to ensure people remain safely and independently in the community.

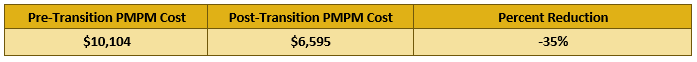

Early Results: HPSM has been able to move nearly 300 members to community settings and achieved a 35 percent decrease in per member per month costs for these members.

Historically, most publicly financed long-term supports and services (LTSS) were provided in institutional settings. In recent years, states have made concerted efforts to enable Medicaid beneficiaries who require LTSS to live in the community. Rebalancing LTSS toward community-based settings can honor individual and family preferences, meet legal obligations under the American Disabilities Act for states to provide care in the least restrictive setting, and reduce state spending. As of 2013, the LTSS balance shifted when, for the first time, states spent more on Medicaid community-based LTSS compared to institutional services.[i]

Dually eligible individuals — those covered by both Medicare and Medicaid — are an important group of LTSS users. More than 40 percent of these individuals use LTSS to meet their daily self-care needs.[ii] Health plans play a major role in LTSS rebalancing for some of this population through their participation in integrated care programs. In integrated care programs, a single entity manages or coordinates the full set of services (e.g., primary and acute care, behavioral health care, and LTSS) covered by both the Medicare and Medicaid programs for dually eligible beneficiaries. Health plans that participate in integrated care programs have great potential to streamline care experiences and align financial incentives to serve individuals in preferred, lower-cost settings in the community.

PRIDE Case Study

This case study is part of a series made possible by The Commonwealth Fund through the Center for Health Care Strategies’ PRomoting Integrated Care for Dual Eligibles (PRIDE) project, a learning collaborative of nine leading health plans to advance promising approaches to integrating and enhancing Medicare and Medicaid services. Case studies highlight how plans participating in PRIDE are working with delivery system partners to advance innovative care management practices for dually eligible populations.

This case study describes how two health plans in California — the Health Plan of San Mateo (HPSM) and Inland Empire Health Plan (IEHP) — developed programs to successfully transition dually eligible members in need of LTSS from institutional to community settings.[iii] They both participate in CalMediconnect, California’s demonstration under the Financial Alignment Initiative (see Exhibit 1 for more information). HPSM developed its Community Care Settings Pilot in 2014 to support members living in an institution in transitioning back to the community and to help members at risk of needing institutional placement to remain in the community.[iv] After learning about the Community Care Settings Program through the PRIDE project, IEHP launched the IEHP Housing Initiative in 2018. Modeled in part after HPSM’s program, IEHP seeks to provide housing, LTSS, and other support services to members in institutional settings who wish to return to the community, as well as homeless members.

Exhibit 1. Overview: The Cal MediConnect Demonstration, HPSM, and IEHP

Exhibit 1. Overview: The Cal MediConnect Demonstration, HPSM, and IEHP

In April 2014, California implemented the Cal MediConnect demonstration under the federally authorized Financial Alignment Initiative (FAI) for dually eligible individuals in seven of its counties. Under the program, contracted Medicare-Medicaid plans (MMPs) in participating counties receive a capitated payment to provide better coordinated Medicare and most Medi-Cal services to eligible members.[v] Some services, including certain specialty mental health services for individuals with a serious mental illness and home- and community-based LTSS, are carved out of MMPs’ capitation payments and are provided by counties. MMPs and counties are required to closely coordinate provision of these services.

Health Plan of San Mateo (HPSM) is a non-profit health plan in San Mateo County, California. It serves around 145,000 people through Medicaid-only products, other locally funded programs, and an MMP under the FAI demonstration. HPSM serves about 8,900 dually eligible members through its MMP.

Inland Empire Health Plan (IEHP) covers more than 1.2 million members enrolled in Medicaid or Cal MediConnect in Riverside and San Bernardino counties in southern California. IEHP covers approximately 28,000 dually eligible beneficiaries.

Impetus for HPSM and IEHP Programs

Several factors led HPSM to design and launch the Community Care Settings Pilot in 2014. Cal MediConnect’s integrated platform and blended financing gave HPSM the flexibility to design a program to meet the full spectrum of needs of its members. Also, following local nursing facility closures and historical efforts by the San Francisco Health Department to move people to community settings, HPSM discovered through interviews with nursing facility residents that many wanted to leave and could do so with the right services and supports, but they did not have a home to go to. After research to understand what services were necessary to support this work, HPSM issued a request for proposals to identify community-based partners to help design and operate a new pilot program. It selected two local non-profit organizations, the Institute on Aging (IOA) and Brilliant Corners (BC) with which to partner. IOA provides intensive transitional case management and oversight, and BC is a housing agency that manages housing-related and tenancy supports and services. Both organizations were already working together to support care transition efforts in San Francisco, and all three have similar philosophies related to integration and community living. Other local program partners include affordable housing providers (e.g., MidPen Housing and HumanGood), county agencies (e.g., Aging and Adult Services and Behavioral Health and Recovery Services), hospital discharge planners, social workers, and a network of Residential Care Facilities for the Elderly (RCFEs). HPSM provides most of the program funding, but also uses some state and local funds.

HPSM and its partners’ work on the Community Care Settings Program inspired IEHP to create its Housing Initiative in March 2018. Following a presentation by HPSM and partners at a July 2016 PRIDE meeting, IEHP began designing a similar model to reach individuals in institutional settings as well as homeless populations in Riverside and San Bernardino. IEHP initially contracted with IOA and BC as well to bolster internal care management capabilities and develop local housing contacts and housing tenancy expertise. Information about the IEHP Housing Initiative in this case study focuses on efforts to support people in institutional settings.

The overarching goal of both programs is to successfully transition individuals from institutional to stable community settings. In addition, HPSM seeks to:

- Reduce overall per member per month (PMPM) costs incurred by members participating in the Community Care Settings Program during the pre- and post-transition periods by investing in community-based supports and reducing institutional costs;

- Ensure that transitioning members remain in the community for at least 12 months;

- Deliver superior client satisfaction; and

- Maintain key partnerships with community providers through regular collaboration.

HPSM’s partners have mission-specific goals as well. IOA strives to create community-based, cost-effective alternatives to institutional settings for any individuals who want to and can be successful living in the community. BC aims to assign a member to a housing unit after receiving a housing referral within 30 days, and to achieve a 90 percent retention rate for six months after a community transition.

IEHP aims to provide its members with high-quality community-based services and supports and accessible housing, and improve both objective and self-reported measures of health. It aims to enroll 350 people in its initiative, transitioning 150 of that number out of an institutional setting or custodial care in the first two years of operation. BC’s goal is to assign an IEHP member after receiving a housing referral within 90 days for this program.

Key Program Elements

Key elements of HPSM’s and IEHP’s programs include: (1) locating eligible individuals to participate; (2) managing transitions, including finding the actual housing and planning for all service needs; and (3) providing post-transition services, including intensive care management, tenancy support, and other services, to ensure people remain safely and independently in the community. The two plans approached some elements similarly and others differently, which reflects their diverse plan and local market characteristics.

Participant Selection

Identifying the right members who can be successful, healthy, and happy in the community is a critical first step in this process. HPSM and IEHP have developed different approaches to identify and assess the readiness and appropriateness of members to participate.

Identification

HPSM focuses its intervention on three target sub-populations of members, including individuals who:

- Reside in nursing facilities or other long-stay settings and want to move back to the community;

- Are about to be discharged from or have spent fewer than 90 days in an acute care or post-acute care setting and need LTSS; or

- Live in the community, but are at risk of being institutionalized.

Individuals are identified when a representative of a member’s interdisciplinary care team (ICT) submits a referral form to the Community Care Setting Program. HPSM reviews all community referrals and uses a case-mix indexing tool developed by the three partners to make initial eligibility decisions and determine priority of enrollment.

IEHP’s in-house long-term care (LTC) management team, primarily comprised of social workers, receives a daily data feed of eligible members from nursing facilities. Potentially eligible members have at least one chronic physical and/or behavioral condition that can be safely managed in the community, and a desire to move. LTC care managers identify potential eligible members, and then interact regularly with nursing facility staff to select members for eligibility consideration.

Assessment

IOA assesses the recently identified HPSM members using criteria to determine who could be successful in the community, including functional status, the individual’s desire to move, social support systems, the availability of appropriate services in the community, and safety. After increased demand created the need for a waitlist in 2017, HPSM added a risk acuity component to the assessment to prioritize individuals for participation. Following the assessment, IOA prepares a case summary for potentially eligible members and presents its recommendations to a Placement Team comprised of staff from HPSM, IOA, and other individuals directly involved in the members’ care. The Placement Team finalizes eligibility decisions and determines the member’s level of care.

At IEHP, a representative from the LTC team meets in-person with potential candidates along with family members and, as needed, other representatives from the member’s ICT such as staff from nursing facility care teams, behavioral health, and care management. Once the ICT members agree that the member is clinically, functionally, and socially able to participate, they are approved.

Transitions to the Community

HPSM has found that the transition process lasts about three to six months. Once a member is identified, the IOA care manager meets regularly with the member and the ICT team to design a care plan and identify the least restrictive community housing option in which the member is likely to succeed. These options may include RCFEs, which are assisted living facilities that have customized supportive services and staff available 24 hours a day. These also include affordable housing, and scattered site (independent) housing, which BC helps to identify. Prior to discharge, HPSM convenes a Core Group, comprised of representatives from the three partners as well as San Mateo County’s Behavioral Health, Aging and Adult Services, the nursing facility, and the individual and his/her family as appropriate, to help address potential challenges with the community placement and other needs to support a smooth transition. Following a discharge from the nursing facility, the partners coordinate housing tenancy services, medical care, and connections to community services via frequent visits from a care manager.

IEHP staff manage the transition process, which usually takes three to four months for individuals residing in an institutional setting. LTC care managers work with BC to determine whether an independent setting or RCFE is most appropriate for each individual.

Both plans have worked through challenges that often arise during the transition period related to housing availability, the complex needs of their members, and internal capacity, including:

- Lack of access to affordable housing. This is identified as the most pressing issue by both plans. In addition to scarce supply, housing units often require physical accommodations, such as space for a walker or wheelchair and options for adaptable technology, which requires BC to take new approaches in identifying units for these members. Also, HPSM initially anticipated that newly transitioned members would prefer to live in independent housing, but many members strongly preferred assisted living and now nearly two-thirds of participants reside in RCFEs. HPSM and IOA, which manage contracting for these often smaller, local entities, now face a limited availability of RCFEs. IEHP manages RCFE contracts and has a slightly different challenge: while it originally contracted with RCFEs to support members age 65 and older, the housing initiative also targets younger people. The plan has broadened its network to identify facilities that accept younger members who may need different resources.

- Complex care and process management. Managing the multiple components of transitions, including securing medical, community-based services, and housing supports, is an incredibly complex endeavor that requires considerable planning. Plans and partners report that there is no formula or routine process to follow, as each member has different needs, and many have chronic conditions, take multiple medications, or have functional limitations. There is a natural pressure in the process to place people as quickly as possible while ensuring that all services are arranged. Along with getting appropriate clinical, housing support, and social services in place, member readiness to move can impact community longevity.

- Need to adapt approaches over time. During early program years, HPSM primarily targeted members with lower care needs. Over time, the needs of individuals targeted for the program have expanded, and many people require additional supports to live in the community. Also, once members moved, both plans were initially surprised by the degree of loneliness and isolation the members reported. While living in facilities, members had been used to following a set routine and seeing the same people every day. In their new residences, they needed additional supports to feel comfortable. In response, HPSM developed a program called Connect for Life with an organization called Wider Circle. This group brings together members to socialize, solve problems together, and build support networks. They have engaged nearly 500 people in this effort.

- Staffing levels. Both HPSM and IEHP are focused on retention and recruitment to ensure they have the right staffing to address members’ unique needs. HPSM works closely with IOA and BC to identify areas in the transition process that would benefit from additional staff, including reviewing bi-weekly data dashboards to identify program gap areas. Last year, HPSM created new positions for IOA to support operations — a program development specialist and a licensed clinical social worker/ clinical supervisor — with the goal of improving internal staffing stability. IEHP has bolstered staffing for its LTC team by adding new social workers and administrative and financial staff to manage contracts and other supports. IEHP has also assigned nursing and social work staff from the housing team to support this effort and coordinate with case management teams.

Post-Transition Services

After members are in a new home, plans and partners work together to provide a wide range of services and supports to maintain independence. For both plans, BC plays an important role in managing housing-related issues, such as landlord disputes, disruptions with Section 8 voucher expirations following hospitalizations, and adjustments to ensure that homes remain safe and accessible following functional status changes. HPSM works closely with IOA to manage additional supportive services such as In-Home Supports and Services (IHSS; see Exhibit 2), nutrition services, and transportation assistance. Community Care Settings Program participants receive an average of 200 days of intensive case management services post-transition. IEHP manages post-transition services internally with a small group of staff from LTC and housing teams, as well as medical case management staff to help manage clinical needs. IEHP noted that its LTC teams have been able to set up members with needed IHSS very quickly.

Both plans meet regularly with providers and the ICT team to review progress, adjust the care plan as needed, and use Care Plan Option (CPO) services to support their members (see Exhibit 2). HPSM and other Placement Team staff present to the Core Group at discharge, and then 30 days, 90 days and six months post-discharge to report on care plan progress. IEHP conducts formal reviews at six and 12 months with ICT case conferences to review progress.

Exhibit 2. Select Medi-Cal Long-Term Services and Supports

Exhibit 2. Select Medi-Cal Long-Term Services and Supports

In-Home Supports and Services

In-Home Supports and Services (IHSS) is a Medi-Cal program that provides domestic, paramedical, and personal assistance services for people with disabilities so that they can live independently or maintain employment safely. The IHSS program provides an alternative to living in an institution for many people.

Care Plan Option Services

MMPs may provide Care Plan Option (CPO) services at their discretion to dually eligible members. CPOs are LTSS that are not covered under Medi-Cal, but that can enhance care, help to keep individuals at home, and/or prevent costly and unnecessary hospitalizations or prolonged care in institutional settings. CPOs are not currently included in the capitated payment rates that MMPs receive. Examples of CPOs include, but are not limited to: respite care in or outside of the home; nutritional assessment, supplements and home-delivered meals; home maintenance and minor home or environmental adaptation; and “other services” that may be deemed necessary by the health plan.

Results

Both HPSM and IEHP are evaluating program results. IEHP is still in the planning phase for its evaluation work, and will contract with a third-party evaluator in late 2020 to examine: (1) access to and outcomes related to preventive care; and (2) utilization of inpatient, primary, and acute care, behavioral health services, and pharmacy. The plan will also collect data on self-reported heath measures and conduct qualified interviews with members.

HPSM began collecting data in 2016 with support from its partners at six-month intervals to evaluate progress toward its goals. As of September 2019, 289 members had participated in the Community Care Settings Program. Seventy-eight of these members were in a skilled nursing facility and placed back in the community; 123 were residing in custodial long-term care; and 88 were already in the community but were at-risk of being institutionalized without additional supports.

HPSM has data on spending and utilization from 2018. Exhibit 3 provides data for the 176 members that, as of June 2018, had at least six months’ worth of longevity in the community. The average PMPM costs for these members in June 2018 was $6,595, a 35 percent decrease from $10,104 in 2014. The members residing in an institutional setting who were moved to the community achieved the largest savings. Costs often increased, however, for the members already in the community but at-risk of institutionalization, though the data does not include the avoided costs for members who may have otherwise entered an institution without this intervention.

Exhibit 3: HPSM Six-Month Pre- and Post-Transition Costs, August 2014-June 2018

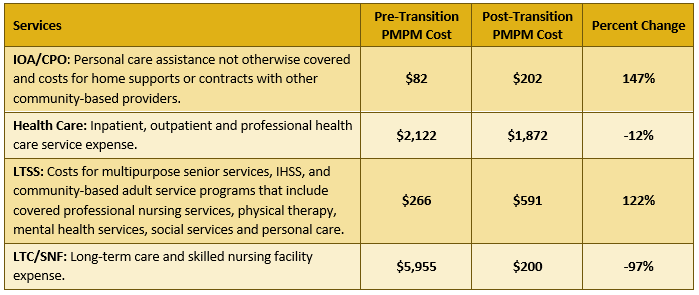

Exhibit 4 shows changes in PMPM costs by service type, six months before and after the 176 individuals transitioned to the community. Investments in community-based LTSS and plan-funded CPO services drove reductions in institutional utilization as well as lower medical spending. IOA posited that the decrease in spending for both LTSS as well as health care utilization resulted in part from an increased motivation of members to take control of their health once they were back in the community. They had a new incentive to “restart” and were motivated to be self-directed and adhere to their medical and social support regimens. This was an unanticipated result achieved for many people.

Exhibit 4: HPSM Six-Month Pre- and Post-Transition Costs by Service Type, August 2014-June 2018

Almost all — 98 percent — of program participants have remained in the community for at least six months. As of June 2018, 93 percent of all program participants have remained in the community regardless of their duration in the program. Most of the reasons for returning to a facility were due to changes in medical conditions. Lastly, member satisfaction with the program has remained high, with about 85 percent of participants saying they were “very satisfied” and “somewhat satisfied” with the program across different reporting periods. The number of program participants who would recommend the program to others rose to 95 percent in 2018 from 90 percent in 2017.

Insights to Guide Program Success

These two California-based programs offer helpful perspectives for health plans, providers, or states seeking to implement a similar model in states across the nation. Below are several insights from PRIDE plans and provider partners about building strong collaborative programs; clarifying roles for each partner; tackling challenges with securing affordable housing; establishing leadership commitment; and managing financial constraints.

Build strong, collaborative relationships between health plans and community partners.

All parties point to the partnerships between health plans and community-based organizations as critical to success and the vehicle to expanding community capacity to meet individuals’ complex needs. Regular communication strengthens collaboration. For the Community Care Settings Program, HPSM, IOA, and BC have bi-weekly meetings to review data on a shared dashboard to identify and troubleshoot issues, and provide feedback on specific cases. IOA and BC also meet separately on issues requiring coordination of care management and housing services expertise. Regular team meetings have helped the partners to build strong relationships, streamline communication, and hold each other accountable to address specific issues.

Furthermore, HPSM, IOA, and BC described the importance of establishing aligned program philosophies around managing transitions and risk tolerance. Clinical health plan staff may have different beliefs about when an individual can safely move from an institutional setting compared to community-based providers or other health plan staff with LTSS backgrounds who are focused on moving people into the least restrictive setting possible. Striking a balance on the right amount of risk between clinical safety and independence was an initial struggle, but it was necessary to develop a shared philosophy about which members were good candidates for successful transition to the community.

Clarify roles and responsibilities for a complex, multi-faceted undertaking.

Since these programs have several moving parts, having clear roles for responsibilities across different functions is important. Health plans and partners involved in these programs are transparent and collaborative as they identify the capacities that each brings to the programs, as well as areas where they depend on other partners. IOA and BC note that HPSM’s initial request for proposals was helpful in this area because it outlined the functions that HPSM sought to contract out. One key decision point for health plans is to determine the extent to which they will provide or pay for care management services. This distinction is important for provider partners to understand their role versus the health plan’s responsibilities. Health plans should consider: (1) the amount of internal resources they can devote to providing complex care management versus managing contracted groups to perform these functions; (2) the availability they have to be in the members’ home; and (3) how closely they can work to connect members to community services.

In this case, IOA and BC note that health plans generally have more ability to bring multiple stakeholders together to develop consensus around new ideas and affect systems change. Community-based providers have key roles in this collaboration, but often lack the influence that health plans bring to the table. Health plans are also in a unique position to align disparate LTSS and the health system in ways that improve and simplify access to services and reduce inefficiencies and duplication.

Both HPSM and IEHP oversee and manage the programs, and both outsource the majority of housing and tenancy-related functions to BC. However, due to different organizational priorities and capacities, they approach care management differently. HPSM recognized IOA’s deep care management expertise and community connections, and thus contracts with and delegates most care coordination and management functions to them. IOA has since embedded a psychologist, nurse, and other key staff in the ICT to support this work. IEHP determined after initial program launch that it could manage social and medical case management services internally, and has since brought those functions back to its LTC and medical case management teams.

Recognize that housing is a “new frontier” for health plans.

Finding affordable, accessible, permanent housing is the top challenge, and identifying these resources takes ongoing investments in time, infrastructure, and leadership commitment. Locating housing units and providing tenancy-support services are also the areas in which both HPSM and IEHP have the least amount of experience, and where BC has provided invaluable support to their work. They recommend that other health plans pursuing similar programs take careful inventory of internal capacity and expertise in this area, and be prepared to contract to fill in any gaps. However, plans should also be willing to put in the time to learn about these services themselves so they can be productive partners. In addition to working with BC, HPSM and IEHP have developed relationships with their local housing agencies. Opening communication channels with different housing stakeholders can also inform plans’ understanding of the complicated local funding sources that support housing. Having a better understanding of local structures has uncovered opportunities where state or local funding could be used, allowing plans to refocus funds on care management, medical, and social supports. For example, HPSM has used Provider-Based Assistance Program Section 8 vouchers to help house members, with the support of the local Housing Authority and BC.

BC noted that HPSM has recently become more focused on securing units in San Mateo’s set-aside affordable housing for seniors. This allows members to hold the lease for these units, and BC provides supportive services to help members navigate that process. Allowing members to hold a lease encourages housing permanency, and also potentially lowers HPSM’s costs by accessing other funding to secure affordable housing.

Commitment to the work must be sustained and through the highest organizational levels.

Patience is an important attribute for managing these programs. Successfully transitioning members who had been receiving comprehensive supports in an institutional setting and who typically have complex needs often takes much longer than expected. Getting these programs up and running is a slow process, and HPSM had to revise its initial targets. In addition, ongoing attention must be paid to medical, behavioral, functional, and social needs through regular assessments, with partners able to identify social needs that might not present clinically and a willingness to address new needs that arise. IOA mentions that HPSM’s Wider Circle Program is an example of diligently identifying and addressing members’ needs that do not present clinically. Furthermore, providing comprehensive wraparound and housing support services is a major investment that needs to be evaluated regularly. For example, the higher demand for RCFE services, which are currently not included in the state’s payment rate to plans, required HPSM to reset how it allocated program resources.

Lastly, these programs require sustained leadership support. The health plan and community partner leadership championed the programs since the beginning. They have also been willing to work with program staff to fill staffing gaps, reallocate investments to better target them, and bring executive-level morale to support difficult work.

Understand the challenges with achieving return-on-investment for health plans.

Although HPSM has produced overall savings, these savings do not reflect its investments in CPO services — such as assisted living (RCFE) and home-care funding for those who cannot manage an IHSS provider — which come from the health plan’s reserves and are not included as part of its capitation rate. Furthermore, reductions in spending on covered services from investments in CPO services can lower calculations for future capitation rates that are based in part on health plan spending experience. Thus, much of cost savings may not accrue to the health plans that make the investments.

Although both plans intend to continue these programs as long as they are able to do so, this is a barrier to expanding current programs and replicating others. On October 29, 2019, California’s Department of Health Care Services released a proposed framework for its upcoming Medicaid waiver renewal, referred to as California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM).[vi] One of CalAIM’s many delivery system reform proposals is to allow Medi-Cal managed care plans to use in-lieu-of-services, which are medically appropriate, cost-effective substitutes to a Medicaid covered services, to close gaps in State Plan benefit services, and address combined medical and social determinants of health needs and avoid higher levels of care. In most cases in-lieu-of services may be included to calculate the medical portion of managed care capitation rates. Before CalAIM’s release, plans and partners had suggested that more flexibility for plans to provide in-lieu-of services could allow plans to capture some of their investment and help to keep people at home. This could also encourage more take-up with other plans and community partners. Potential in-lieu-of-services in the CalAIM proposal that are relevant to these programs include housing transition and navigation services, housing tenancy and sustaining services, and nursing facility transition/diversion to assisted living facilities or home.

Another financial challenge is that most of HPSM’s savings are due to moving residents out of institutions, but the Community Care Settings Program also targets members in the community who are at risk of being moved to an institution. Investments to keep individuals at home may initially increase spending, and plans do not have a way to demonstrate the potential cost savings from avoiding a future nursing facility placement. This could deter plans from investing in this population, which has clinical as well as financial implications. IOA notes that once people move to nursing facilities, they are more likely to lose their community housing, connections to the community and have less motivation to return. Plans and provider partners would like to use these programs as a vehicle to deter nursing facility placements for this population.

Finally, IEHP noted it is important to take start-up (i.e., pre-transition) costs into account when evaluating these programs. When IEHP conducts its evaluation, it intends to consider these costs to calculate a more holistic return-on-investment of its program.

Conclusion and Next Steps

Designing and operating interventions to transition people with high needs out of nursing facilities and back to community living is a comprehensive endeavor that requires coordination across — and unique expertise from — multiple stakeholders. The quantitative and anecdotal results from HPSM’s Community Care Settings Program make the case for investing in this important work, as well as provide the impetus for similarly mission-driven health plans like IEHP to design a similar model. Both plans are focused on ways to demonstrate the value of and sustain their programs. HPSM will continue to evaluate the program’s successes. In the near future, HPSM will focus on improving program efficiencies and developing real-time responses to emergency department utilization. It is also exploring how to stratify risk across the community-dwelling population at risk of institutionalization to ensure the right interventions are in place. IEHP is continuing to build relationships with local housing stakeholders and identifying new members who may benefit from moving home.