In 2013, just over 850,000 homeless patients visited 250 federally funded Health Care for the Homeless health centers that specialize in homeless health care; of these individuals, 57 percent were uninsured. With 30 states (plus Washington, D.C.) extending Medicaid benefits to low-income people through the Affordable Care Act (ACA), more people who are homeless — living on the streets, in shelters, and doubled up with family and friends — now have access to health insurance, many for the first time. Lessons from health centers serving homeless populations can guide the broader health care community in helping this vulnerable group obtain and effectively use health insurance.

To examine the impact of Medicaid expansion on individuals who are homeless and the providers who serve them, the Kaiser Family Foundation partnered with the National Health Care for the Homeless Council to conduct focus groups with administrators, clinicians, and enrollment workers at Health Care for the Homeless (HCH) projects in Florida, Illinois, Maryland, New Mexico, and Oregon. Feedback from HCH providers and staff in these states reveal challenges and opportunities in six areas:

Outreach and Enrollment

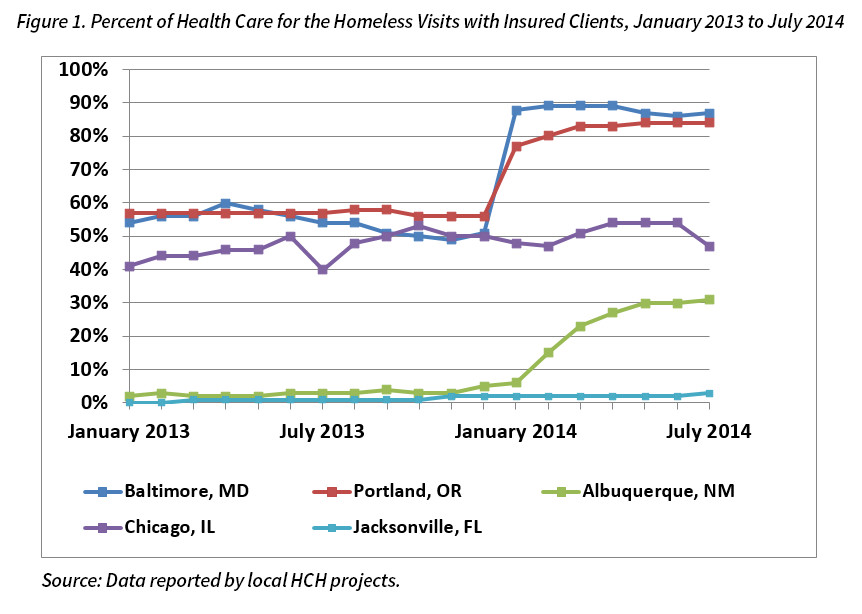

In states that expanded Medicaid, HCH providers saw gains in health insurance among people who are homeless. States with the sharpest increases in enrollment took advantage of options to facilitate enrollment. Florida did not expand Medicaid and saw little change in enrollment.

Using an outreach approach that includes homeless shelters, encampments, soup kitchens, and other non-traditional sites, HCH enrollment workers report that nearly all homeless individuals they come into contact with are eligible for Medicaid and are excited to sign up for coverage. Indeed, many specify the care they intend to seek out, with addiction treatment, surgeries, and dental care often mentioned as the top priorities.

Using an outreach approach that includes homeless shelters, encampments, soup kitchens, and other non-traditional sites, HCH enrollment workers report that nearly all homeless individuals they come into contact with are eligible for Medicaid and are excited to sign up for coverage. Indeed, many specify the care they intend to seek out, with addiction treatment, surgeries, and dental care often mentioned as the top priorities.

Benefits to Clients

Medicaid eligibility helps patients who are homeless connect to a broader range of needed services, particularly for specialty care and residential drug treatment. Providers also report that patients who are newly covered are noticeably more empowered to participate in health care decisions. They also note that accessing a regular source of care helps newly covered patients document functional impairments — a key requirement when applying for Social Security disability benefits. Prior to the ACA’s Medicaid expansion (and currently in states that have not expanded to adults), the typical pathway to Medicaid eligibility for adults was to meet Supplemental Security Income benefits by virtue of a qualifying disability.

Benefits to Providers

Providers are better positioned to create consistent care plans for homeless individuals who have health insurance coverage. Previously, safety net clinics serving uninsured patients would often rely on inconsistent medication samples, limited pro bono services, and other ad hoc and grant-funded arrangements that changed frequently. Additionally, third-party reimbursement from Medicaid is more predictable than grant funding, allowing community-based HCH health centers to hire additional staff and focus on quality improvement.

Approaches to Care

Providing case management and supportive services as well as a non-judgmental, trusting, and integrated care is critical when engaging individuals who are homeless. This means ensuring that primary care, mental health, addiction, dental, case management and other services are delivered by professionals familiar with motivational interviewing, trauma-informed care, assertive community treatment, and other evidence-based practices. Despite state options to add specific services to benefit packages (such as 1915(i) and/or health homes), most states still do not cover case management or other support services, making traditional safety net funding sources of ongoing importance to fill gaps in services.

Relationship of Housing to Health Care

Services are less effective when patients are living on the street, in shelters, or “couch surfing.” Addressing social determinants of health — like the lack of housing — must be part of the larger health care conversation. While an illness can cause homelessness, so too can homelessness cause new or exacerbate existing health conditions as well as make it difficult to adhere to medical plans. Ample research demonstrates that accessing housing improves health and lowers costs.

Role of Managed Care

Some aspects of managed care may create barriers to care for homeless patients. When beneficiaries are auto-enrolled into plans or auto-assigned to unfamiliar providers in a distant section of town, they may have difficulty accessing care. In-network providers may not be equipped or inclined to treat the complexities and social issues inherent to homelessness. Requirements for prior authorizations on prescriptions or other services and frequently changing drug formularies also create barriers to timely treatment, especially for behavioral health conditions.

Looking Ahead

Based on the early Medicaid expansion experiences of health care providers serving homeless populations, key areas of focus include:

- Expanding Medicaid. Absent Medicaid expansion, states cannot provide most of the opportunities outlined above.

- Ensuring continuity of enrollment and assignment. HCH enrollment workers are focused on ensuring that clients connect with willing providers of choice and do not “fall off the rolls.”

- Educating providers, clients, and plans. Understanding how to use Medicaid benefits, creating care plans that include covered services, and learning more about the needs of this patient group should be priorities for all stakeholders.

- Sharing data across providers. Improving quality and care coordination demands access to data systems that unite utilization, health outcome, and cost data across all care settings

- Addressing social determinants of health. Health reform offers a renewed opportunity to better connect health outcomes to housing stability.

- Keeping safety net funding streams. Medicaid does not typically cover the broad range of services a homeless population needs, making traditional grant funding critically important to close gaps in services.

- Enhancing workforce capacity. Recruiting and retaining the full range of service providers needed to meet the complex health care needs of vulnerable populations is critical, and requires investments in staff and training.

The early experiences of health care providers serving homeless populations with Medicaid expansion reveal new opportunities for maximizing Medicaid’s role in improving health outcomes, especially for vulnerable and chronically ill populations. As states move forward, these lessons can inform policy and practice decisions.