Program Snapshot

Name: AccessHealth Spartanburg

Goal: Improve health care outcomes and reduce health care costs for Spartanburg County’s highest utilizers of uncompensated care by connecting uninsured adults to primary care providers and community services.

Featured Services: Dedicated community case manager and a case severity tool that uses medical and psychosocial markers to stratify clients into low-, moderate-, and high-risk categories. Clients are assigned a case manager and offered interventions based on their risk “score.”

Target Population: Participants must have: (1) one or more diagnosed chronic conditions; (2) no insurance; (3) an income at or below 150 percent of the federal poverty level; and (4) utilized the hospital within the last 12 months.

In Spartanburg County, in the northern part of South Carolina, roughly 18 percent of non-elderly adults are uninsured, including a significant portion who experience multiple hardships such as poverty, chronic illness, mental health needs, poor access to primary care, and other barriers to health. Roughly one-third of Spartanburg’s most medically and socially complex patients are also caught in a coverage gap — they have too much income to be eligible for the state’s Medicaid program, but are too poor to qualify for federal health insurance subsidies available under the Affordable Care Act. When these individuals do seek care they are often in crisis, resulting in multiple and costly visits to the emergency department (ED) and frequent hospitalizations.

In 2013, as an alternative to Medicaid expansion, the South Carolina legislature offered all hospitals in the state a deal in exchange for reducing the soaring costs of uncompensated care. Hospitals that agreed to enroll their costliest patients in the new Healthy Outcomes Plan (HOP) — a health care delivery model focused on coordinating care for chronically ill, uninsured individuals who are high utilizers of hospital and emergency department (ED) services — could receive a 2.5 percent increase in their Medicaid reimbursement rate. Half the funds resulting from the increase were earmarked for the HOP program. Hospitals choosing not to participate stood to have their disproportionate share payments (federal payments to hospitals that serve a large number of Medicaid and uninsured individuals) reduced by millions of dollars per hospital. This led many hospitals to partner with local organizations specializing in complex care management.

One such organization, already operating in Spartanburg since 2010, was AccessHealth Spartanburg (AHS). AHS specializes in helping uninsured, low-income individuals coordinate their health care and connect to community resources. It accomplishes this through a network of 10 community partners, including two local hospital systems (Spartanburg Regional Health Care System and the smaller, private, Mary Black Hospital System); the county’s drug and alcohol commission, as well as its Department of Mental Health; and Welvista, a statewide prescription assistance program. AHS also has relationships with numerous local nonprofits, including food banks, farmers’ markets, shelters, and more. Physicians volunteer their time and provide AHS clients with free medical care at area clinics and hospital-affiliated practices

In 2013, Spartanburg Regional Health System and Mary Black Hospital gave AHS $1 million in HOP funding in exchange for serving an initial 487 Spartanburg County residents identified by the state’s Department of Health and Human Services as the county’s highest utilizers of charity care. Due to the program’s success, funding has continued every year since then. To qualify for case management under AHS’ HOP program, clients must be uninsured, have an income below 150 percent of the federal poverty level, and have at least one chronic condition such as high blood pressure, diabetes, or a behavioral health need — although the majority have multiple chronic conditions. Individuals eligible for HOP are also frequent users of hospital services, defined by the state as having three or more ED visits in the last year, or a combination of an ED visit with a hospital admission or unplanned readmission. “We give clients a card that looks like any insurance card identifying them as part of the program with an expiration date for a year later,” says Carey Rothschild, AHS’ executive director. Although there is no time limit for how long people can be enrolled in AHS or HOP, at the end of a year, clients must demonstrate they still qualify in terms of income, insurance status, and medical need.

“The Health Outcomes Plan model was an opportunity to put our program on steroids.”

In 2014, AHS was selected to participate in the Transforming Complex Care initiative, made possible through support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. AHS hired a new community case manager (aka community health worker) to provide services to the additional HOP patients, who primarily have lower medical needs but higher psychosocial needs. The added manpower was, as Rothschild says, “an opportunity to put our program on steroids.”

COMPLEX CARE INNOVATION IN ACTION

This profile is part of an ongoing series from CHCS exploring strategies for enhancing care for individuals with complex health and social needs within a diverse range of delivery system, payment, and geographic environments. LEARN MORE »

Innovating Case Management

As part of the Transforming Complex Care pilot, AHS has been pursuing several case management approaches, including allowing case managers extra time to build rapport with clients, and finding the “sweet spot of how many people can really be on a caseload and still be successful,” says Rothschild. AHS also developed a case severity screening tool that uses 18 weighted medical and psychosocial markers to stratify clients into buckets of low-, moderate-, and high-risk categories. During the initial enrollment visit, which usually takes place in a client’s home, case managers conduct the severity screening as well as a social determinants of health (SDOH) assessment to determine the level of unmet social needs.

All information obtained from the screening tool is entered into AHS’ electronic case management system, where a severity score is generated and used to determine client goals and a timeline for meeting them. The client’s severity level also determines whether they are assigned to a registered nurse case manager (moderate-to-high severity), social worker (moderate severity), or community case manager (moderate-to-low).

AHS Case Severity Screening Tool: Sample Questions

MEDICAL

- Have you recently been hospitalized or had surgery?

- What medical programs have you been diagnosed with?

PSYCHOSOCIAL

- Do you have any issues affording your medications?

- Are you homeless?

- Have you been released from jail in the last year?

- Does your phone number or address change frequently?

(Additional questions measure factors such as health literacy, drug and alcohol use, and food security.)

“We create interventions to try to improve a client’s severity level over the next six months,” says Summer Tebalt, a registered nurse case manager for AHS. “If the severity level is high, the intervention is likely going to be something along the lines of: connect with a primary care provider (PCP) within the first two weeks, make weekly phone calls until the client gets in with a PCP, make a home visit within the first month, and get the client food stamps or into a homeless shelter within a certain time frame.” If a client has mental health issues, Tebalt and other case managers will facilitate a connection to services through the state’s mental health department. As case managers learn about additional needs — substance use issues, for example, are often not disclosed until several months into a client-case manager relationship — these are entered into the case management software and new goals for intervention are established.

Tebalt currently manages the care of about 100 clients who are in the moderate-to-high severity category, which includes individuals with significant medical, behavioral health, and social needs. Tebalt typically accompanies clients to their first primary care appointment, as well as their first three mental health appointments. She is also available to help clients with a range of interventions tailored to meet their individual needs — for example, working with them to fill a weekly pill planner or applying for food stamps.

Extending Community-Based Case Management and Training Tomorrow’s Workforce

“I think most of the students are uncomfortable at first with not having all the answers. The solutions to their clients’ problems are not always black and white. But, that mirrors reality, and prepares them well for a career in medicine.”

Because of the great need within Spartanburg, AHS is continually searching for new ways to stretch the capacity of its community-based management services. In response, AHS recently partnered with the Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine (VCOM), to extend case management capacity with second-year medical students. During an initial meeting supervised by a case manager, the student completes the health screenings with an assigned AHS client. From there, students meet with clients at least weekly, and help them progress toward health goals. The program serves the dual purpose of extending the reach of the case managers, and providing future health care providers experience with individuals who have complex medical and social needs.

Because the participating students are in training, only low-to-moderate risk patients are involved in the program. However, the experience they receive is invaluable: “I think most of the students are uncomfortable at first with not having all the answers,” says Rothschild. “The solutions to their clients’ problems are not always black and white; there’s an amount of gray. But, I think that mirrors reality, and prepares them well for a career in medicine.” The initial pilot efforts were so successful, AHS and VCOM chose to continue the program with a new cohort of students in March 2018.

Building Relationships and Connecting Clients to Services

A large part of what makes AHS successful is building relationships with clients and establishing trust. “We start building that relationship as soon as we start asking questions about unmet social needs, and we let them know that we are only asking so that we can get them help,” says Tebalt. “I hold my clients accountable for their health and show them how they can use the resources we provide. Encouraging that accountability empowers them to become more involved in their health.”

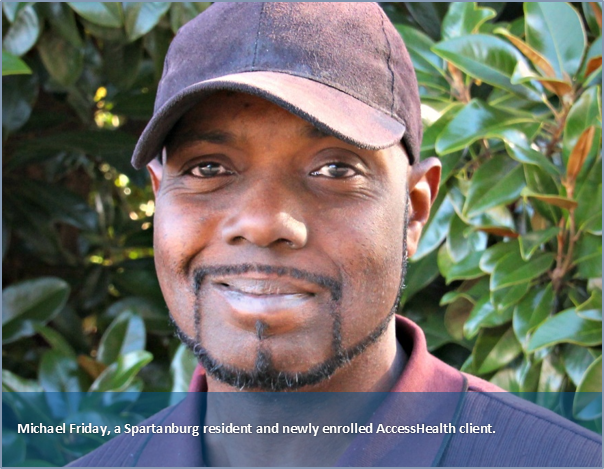

The impact of this highly engaged case management model can be enormous. In July 2017, Tebalt met a new client, Michael Friday, who had just been discharged from his fifth hospitalization in five months. At 39, Friday, a native of Trinidad, had contracted a virus that led to congestive heart failure. “In the process of being hospitalized for so long, he lost his job, was evicted from his mobile home, and had no money to buy his medications,” says Tebalt. Having few local friends or family to call upon for support, the results were devastating — Friday ended up homeless, and as a result, lost custody of his children. He was referred to AHS, which quickly connected him to housing in a local homeless shelter and worked with him to get his medications. Within two weeks of being enrolled in AHS, Tebalt accompanied her new client to his visit with a PCP, the congestive heart failure clinic at the hospital, and a cardiologist. With Tebalt’s assistance, Friday was able to secure a long-term supply of affordable prescription drugs, get signed up for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, and purchase heart-healthy foods. Three months later, the man’s disease was under control, he had not been back to the ED, and he had reconnected with family living in the Northeast. Friday is now working and saving money for a place where he and his children may live. “He’s been very successful, very engaged, and really motivated,” says Tebalt.

Cartia Higgins, the community case manager hired under the TCC grant, manages the care of about 60 low-to moderate severity AHS clients, including individuals with high blood pressure or other medical conditions, and untreated mental health issues. The majority are low-income, have little access to transportation, and face “huge barriers” to care. “Many of my clients are homeless,” says Higgins. “They live at a homeless mission or in a tent and because there are few places to obtain free care, some use street drugs to replace medications.”

Higgins speaks with about 25 of her clients weekly, checking in on transportation to and from doctors’ appointments, medication, or simply calling after a provider visit to see how things went. She also makes home visits to assess clients’ living conditions, and often accompanies them to appointments at the mental health clinic or primary care provider. For one unstably housed client — a Ukrainian immigrant who had his leg amputated due to gangrene — home was a series of temporary locations. Higgins met with the man in the library (a common meeting place for her homeless clients), and found out that while he used to do yard work in exchange for housing, his injury left him homeless and unable to afford food or medicines. Through her AHS connections, Higgins located a doctor who agreed to make a prosthesis for her client at no cost. She also contacted a local Russian church that connected the man with a family offering him a studio apartment. “Over the course of three months, my client gained his independence: he got his new leg, started working again, and moved into his own apartment,” says Higgins.

Not everyone has such a smooth path toward independence. Higgins’ toughest clients — including many of those struggling with substance use disorders — sometimes miss medical appointments and inconsistently follow up on other services. Most are very lonely, isolated, and have burned bridges with family or other supports. “I don’t pressure anyone to go to a substance abuse counselor,” says Higgins. “I just put it out there, and tell them, ‘For the first appointment I’ll go with you.’ I stay consistent with them and let them know, ‘I’m staying with you, I’m going to push you and motivate you to move to the next level.’”

Sustaining the Model

The innovations at AHS are supported by Spartanburg’s community-wide movement to address health outcomes with a lens that goes beyond health care. Indeed, in 2015, Spartanburg was one of only eight communities nationwide to receive the prestigious Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Culture of Health prize in recognition for its progress in improving health status countywide. Word has gotten out in this small, close-knit community about the work being done at AHS. “When we first started out, our clients primarily came from ED referrals,” says Rothschild. “Now, about half the people seeking care here come in via word of mouth.”

“When we first started out, our clients primarily came from emergency department referrals. Now, about half the people seeking care here come in via word of mouth.”

AHS staff meet monthly with community partners to keep abreast of local programs and resources, and informal case conferences are held daily to allow AHS’ HOP staff to share their unique perspectives and experiences. Outside of work, AHS employees are required to volunteer in at least one local community organization, such as a local food bank or homeless shelter. This not only keeps employees in-tune with the broader needs of their community, but also widens the network of connections AHS can call upon. Tebalt volunteers at a local farmer’s market, and uses her connections there to teach clients how to find and shop for healthy food. Rothschild’s own dentist began seeing AHS clients after a discussion they had during one of her appointments. This networking (which Rothschild refers to as “capitalizing on serendipity”) reflects AHS employees’ passion for their organization’s mission, and is a powerfully persuasive tool in bringing other partners aboard.

Since beginning operation, AHS has served 8,300 individuals, with an additional 1,757 clients enrolled in AHS’ HOP since 2014. Together, AHS and its HOP program, together with their state and community partners, have had a significant impact on reducing the amount of charity care provided by Spartanburg’s local hospital system. AHS’ case management model and track record of connecting complex clients to a wide range of services are clearly making a difference. “The hospitals get it,” says Rothschild. “That’s why they are reaching out to us to join them under HOP: they have seen the proof.” For further proof, under the TCC grant, independent evaluators are examining AHS’ impact using qualitative interviews and a quantitative comparison of other HOP programs in South Carolina. Rothschild acknowledges the importance of these data: “This way, we can make the economic case for the work we do for our hospital system and the community.”

Author Naomi Freundlich is a journalist with more than 25 years of experience writing about health care.

About the Center for Health Care Strategies

The Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) is a nonprofit policy center dedicated to improving the health of low-income Americans. It works with state and federal agencies, health plans, providers, and community-based organizations to develop innovative programs that better serve people with complex and high-cost health care needs. To learn more, visit www.chcs.org.

About Transforming Complex Care

AccessHealth Spartanburg is part of Transforming Complex Care, a multi-site demonstration aimed at refining and spreading effective care models that address the complex medical and social needs of high-need, high-cost patients. This national initiative, made possible with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and led by CHCS, is working with six organizations to enhance existing complex care programs within a diverse range of delivery system, payment, and geographic environments. For more information, visit www.chcs.org/transforming-complex-care.