Takeaways

- Systemic racism within health care and other social institutions has led to large racial and ethnic disparities in access to health care, poor health outcomes, and high mortality rates for women and children of color.

- Evidence-based home visiting programs can help reduce racial and ethnic health disparities by providing mothers with screenings, case management, family support, and referrals that address a family’s physical, mental, and health-related social needs.

- Using culturally responsive, community-driven, and anti-racist approaches to support underserved, low-income, or at-risk families can help these programs increase opportunities to identify and address racial inequities and disparities, as well as improve maternal and early childhood outcomes.

- This brief explores strategies used by state Medicaid and health agencies in New York, Minnesota, and Vermont to improve equitable health and well-being outcomes through their home visiting programs.

There are gaping disparities in maternal and early childhood health outcomes within communities of color. The Black community, in particular, is severely impacted by racist systems, policies, and practices that reduce access to health care and impede effective treatment — resulting in worse maternal and child health outcomes than other racial and ethnic groups. The mortality rate for pregnant Black women is four to five times higher than it is for white women over the age of 30, even when controlling for education.1 Black infants are more than twice as likely to die within the first year of life as white infants.2, 3, 4 Native Americans/Alaska Natives, Asian Pacific Islanders, and subgroups of Latina women and children also fare worse than white families when it comes to maternal and child health outcomes.5

Evidence-based home visiting programs offer a proven track record in addressing or at least mitigating disparities in health care quality and health outcomes by coordinating care and referrals to a variety of services, including other early childhood care and education programs.6 When home visiting programs use culturally responsive and community-driven approaches to support underserved, low-income, or at-risk families, they can be even better positioned to address racial and ethnic disparities and improve maternal and early childhood outcomes.7 This brief explores strategies used by state Medicaid and health agencies in New York, Minnesota, and Vermont to improve equitable health and well-being outcomes through home visiting programs. While this brief primarily focuses on Black women and their young children, the strategies discussed can benefit all mothers and children of color. The featured states participated in Aligning Early Childhood and Medicaid, a national initiative led by the Center for Health Care Strategies with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation that aimed to enhance alignment across Medicaid and state agencies responsible for early childhood programs with the goal of improving the health and social outcomes of infants and children in low-income families.

Maternal Provider Implicit Bias: Consumer Perspectives

Research shows that health care providers spend less time with Black patients, ignore their symptoms, minimize their concerns, and undertreat their pain. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has recognized that racial and ethnic biases contribute to disproportionate pregnancy-related deaths among women of color and has put forth recommendations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. The New York State Department of Health conducted listening sessions to learn about implicit biases Black mothers face in prenatal, delivery, and postnatal care. Their findings reinforced the prevalence of such biases:

Research shows that health care providers spend less time with Black patients, ignore their symptoms, minimize their concerns, and undertreat their pain. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has recognized that racial and ethnic biases contribute to disproportionate pregnancy-related deaths among women of color and has put forth recommendations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health and health care. The New York State Department of Health conducted listening sessions to learn about implicit biases Black mothers face in prenatal, delivery, and postnatal care. Their findings reinforced the prevalence of such biases:

- “Because I’m Black, [they think] my baby’s father is in jail.”

- “When I feel myself getting really frustrated, I turn up my white girl voice.”

- “[N]urse came in at 3 a.m. asking what family planning method [the mother] wants to use… Just because she’s Black or Latina, they want to make sure we stop having babies.”

- “Receptionist puts single on the form, automatic assumption because you’re Black.”

- “We’re high risk because we’re Black.”

Home visiting can assist families with young children in connecting to the health and social supports they need. Home visits can also help eliminate assumptions about a family’s life and assure clear communication across their health care team. The Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) program is a federal program that provides funding to states and tribal entities to implement and support evidence-based home visiting programs that best meet the needs of communities. These home visiting models provide pregnant women and families with young children — particularly those considered at-risk — services and resources to raise children who are physically, socially, and emotionally healthy and ready to learn. These programs aim to: (1) improve maternal and child health; (2) prevent child abuse and neglect; (3) encourage positive parenting; and (4) promote child development and school readiness.8

Families that participate in home visiting programs can receive help from health, social service, and child development professionals. Services provided during home visits may include:9

- Supporting preventive health and prenatal practices;

- Assisting mothers on how best to breastfeed and care for their babies;

- Helping parents understand child development milestones and behaviors;

- Promoting parents’ use of praise and other positive parenting techniques; and

- Working with mothers to set goals for the future, continue their education, and find employment and child care solutions.

The benefits of home visiting programs are numerous and two-generational.10 Specifically, home visiting is credited with:

- Increased referrals and enrollment in community services, including family planning, adult education, employment, and transportation services;

- Improved self-efficacy and lower depression rates, as well as decreased pregnancy-related hypertension and fewer delivery complications;

- Uptick in likelihood of breastfeeding and adopting healthy eating habits;

- Decrease in likelihood to drink alcohol or smoke during or after pregnancy; and

- Decrease in likelihood for infants to be born preterm or at a low birthweight and fewer emergency room hospitalizations.

By the Numbers: The Case for Evidence-Based Home Visiting Programs

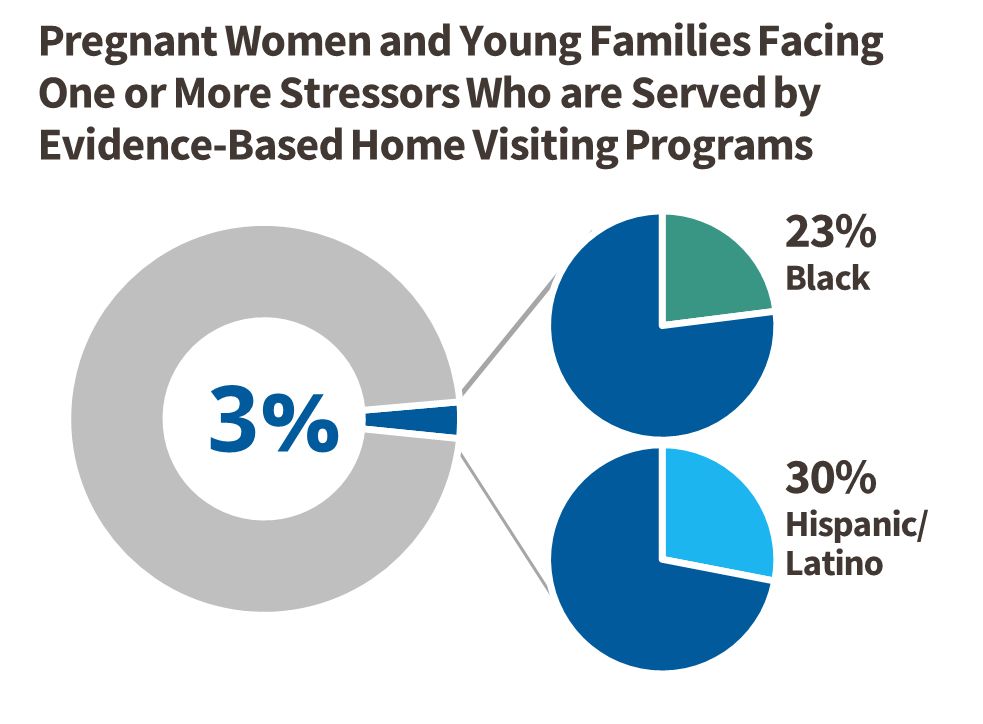

In the U.S., there are more than 18 million pregnant women and families with children under six years old and not yet in kindergarten. About half of those face one or more stressors: raising an infant, having an income below the federal poverty threshold, being single or never married, being pregnant or a mother under 21, and not having a high school diploma.

Of those with one or more stressors, just under 300,000 (3 percent), were served through evidence-based home visiting programs in 2019. There is a need for more funding for the millions of mothers and families in need of supports. Of these families served by evidence-based home visiting programs, 23 percent are Black and 30 percent are Hispanic or Latino, indicating that the need is also there to serve more mothers and families of color. Increasing home visits serving families of color with stressors would help redress maternal and child well-being racial disparities.

Of those with one or more stressors, just under 300,000 (3 percent), were served through evidence-based home visiting programs in 2019. There is a need for more funding for the millions of mothers and families in need of supports. Of these families served by evidence-based home visiting programs, 23 percent are Black and 30 percent are Hispanic or Latino, indicating that the need is also there to serve more mothers and families of color. Increasing home visits serving families of color with stressors would help redress maternal and child well-being racial disparities.

The most recent 2019 Mother and Infant Home Visiting Program Evaluation (from the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation of the Administration for Children and Families) examined the outcomes of select home visiting programs and found no statistically significant differences in health and well-being outcomes across race and ethnicity when home visiting programs were implemented with fidelity.11 This is unsurprising since these programs were not intentionally designed to mitigate racial and ethnic disparities. There are examples of specific models that achieved different outcomes based on the goals they were designed to reach. For instance, looking at two common home visiting service delivery models, each with a distinct focus, Parents as Teachers had the largest increase in parental supportiveness and Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP) had the largest reduction in emergency department visits for children. These results suggest a need for programs to intentionally target racial equity goals to have greater impact on families of color. Expanding quality home visiting programs with anti-racist and culturally competent practices is needed to reach and further support more mothers, infants, and children of color.12, 13, 14 The section below outlines a number of program enhancements that home visiting can adopt to help redress racial disparities in maternal and child well-being.

Home visiting can improve health and well-being outcomes for parents of color and their young children — especially those programs that are evolving their policies and practices to better address racial inequities and health disparities. There are aspects of a home visiting program that, when addressed from a racial justice lens, can help mitigate disparate morbidity and mortality rates even further. Based on research and interviews with state agencies and organizations focused on improving home visiting programs, below are key strategies to enhance home visiting to better address racial disparities, including to:

A critical element of home visiting is the ability to tailor interventions to individual family values, cultures, and needs. For example, Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP) educates staff to always ask about cultural practices as part of home visits.15 During an interview with NFP New York leadership, they shared that some immigrant populations and religious groups do not traditionally shower for the first couple of weeks after birth. In these instances, NFP nurses conducting home visits work with the mother to keep the perineal area clean, while supporting the mother’s personal values. In other communities, placing an amulet bracelet on the baby’s wrist is thought to ward off bad spirits. NFP nurses work with the mother to secure the charm or consider alternative locations that prevent a child from accidentally choking on the bracelet. More generally, when working with communities of color in the United States, NFP nurses are educated to listen, acknowledge, and celebrate different practices during home visits, while simultaneously ensuring the health and safety of the mother and child.

Several recommendations to culturally tailor home visiting to the needs of Black families in particular are compiled in a report to the Minnesota Department of Health Center for Health Equity, generated as part of a funding requirement from the Office of Minority Health.16 Suggestions include developing staff training modules on traditional parenting/nurturing practices, sharing cultural teachings/worldviews, and celebrating all types of family structure (e.g., elder caregivers, extended family). The report also outlines opportunities to engage local institutions, such as Black churches and Black-led organizations, to help incorporate the community’s strengths and challenges into care models.

Culturally tailored home visiting programs exist for select communities of color. For example, the Johns Hopkins Center for American Indian Health developed Family Spirit,17 a home visiting model that is replicated in more than 120 American Indian communities across the United States. The curriculum covers typical home visiting topics around infant care and maternal health, but also incorporates tribal teachings and practices, information about traditional ceremonies related to pregnancy and childrearing, and classes on cradleboards — an indigenous baby-carrying method. In a randomized control trial, outcomes 12 months postpartum suggest that Family Spirit improved parenting and infant outcomes, including parenting knowledge and self-efficacy, children’s psychosocial and behavioral functioning, and home safety strategies, that predict lower lifetime behavioral health and substance use risk for participating mothers and children.18 This strengths-based, culturally informed approach can be adapted to celebrate cultural practices of additional communities of color.

Home visiting should meet families where they are — judgment free. According to the Minnesota Department of Health report mentioned above, “This means providing the services and support based on [families’] individual circumstances, their priorities, and their strengths.16 NFP follows the same tenet, which led to a collaboration with the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene called the Targeted Citywide Initiative (TCI). TCI supports women and teens in shelters, foster care, and the juvenile justice system, as well as women currently or formerly incarcerated, a majority of whom are women of color.19 TCI ensures that NFP nurses have a reduced caseload to better support the transient nature of the families they serve. One of the most transformative aspects of TCI is the ability for NFP nurses to continue working with mothers and children, even if the families move across the city’s five boroughs. Consistency, extended time, and additional capacity to support high-need families are essential practices to help reduce maternal and child health disparities.

The Nurse-Family Partnership Strengths and Risks (STAR) Framework is part of the NFP model and is designed to help nurses and supervisors systematically characterize levels of strength and risk exhibited by the clients and families they serve. While assessing client strengths and risks across 21 measurement categories — based on economic capacity, neighborhood and physical environments, community and social context, and health care system — the STAR Framework is primarily a risk assessment providing NFP teams with a common language and process for characterizing and organizing these strengths and risks.

Tailored interventions can help reduce health disparities for families of color. Across its national programs, NFP uses a strength and risk framework (STAR Framework) that examines categories of well-being to identify ways to build on assets and mitigate challenges. Using this tool, an NFP nurse working with a pregnant teen learned that she ate fast food on most days. The nurse sat with the young woman to review the nutritional information of those fast-food meals and compare it with prenatal requirements. The nurse then helped the teen identify additional nutrition facts for food in her cupboard, eventually putting together a meal plan and grocery list tailored to her culture, taste, budget, and cooking skills. Effective interventions cannot be top-down, cookie-cutter solutions. Individualized, real-time solutions must be co-created with families in a safe, trusting space that adapt to their physical, financial, social, and emotional context at that moment. When working with families from diverse races and ethnicities, it is essential to build on their familiar practices, foods, and language, rather than expect them to change based on information reflecting western cultural bias.

A Story from the Field During the COVID-19 Pandemic

“Meeting families where they are” has taken on a new literal meaning during the COVID-19 pandemic through virtual home visiting. Despite technical challenges, many home visitors nimbly adapted their strategies to remain a steadfast, trustworthy, and reliable support network during this unprecedented time. As research for this brief, one of the co-authors shadowed a virtual home visit in Oregon with permission of the client, Amy. The experience captured the power of the home visiting model to build deep relationships and holistically support families from diverse backgrounds.

“Meeting families where they are” has taken on a new literal meaning during the COVID-19 pandemic through virtual home visiting. Despite technical challenges, many home visitors nimbly adapted their strategies to remain a steadfast, trustworthy, and reliable support network during this unprecedented time. As research for this brief, one of the co-authors shadowed a virtual home visit in Oregon with permission of the client, Amy. The experience captured the power of the home visiting model to build deep relationships and holistically support families from diverse backgrounds.

The visit began with a private check-in with Amy, providing an opportunity for her to share updates, challenges, and successes. Amy had just become eligible for gastric bypass surgery after fulfilling months of requirements, a goal she set with her home visitor after the birth of her second child. Since their previous visit, Amy had also reconnected with her estranged father and was slowly rebuilding trust and developing a healthy relationship. She talked about the boundaries she was establishing and expressed elation at the connection between her children and their grandfather. Lastly, Amy shared traumatic news about her former abuser committing suicide that week. She processed her emotions with the home visitor, Lisa, who listened, asked thoughtful questions, and validated Amy’s mixed feelings.

With so much going on in Amy’s life, Lisa recognized that it was not appropriate to jump into a lesson on child development without first addressing Amy’s pressing needs. Instead, she waited to find a natural pause to ask Amy if she wanted to head downstairs so Lisa could say hello to her 18-month-old daughter. The virtual format did not prevent Lisa from noting developmental milestones as the toddler scurried around the room between her mom and dad, making eye contact with her parents, and showing off her new dance moves. Lisa did not push a particular curriculum on the parents, but rather, addressed the mother’s current needs and used teachable moments to reinforce positive parenting practices or suggest alternatives.

According to recommendations from New York’s Taskforce on Maternal Mortality and Disparate Racial Outcomes, all providers who interact with mothers of color should be trained on: (1) enhanced communication and cultural competency; and (2) implicit bias. In interviews for this brief, leadership at NFP and Healthy Families New York (HFNY) — an affiliate of Healthy Families America (HFA), another leading evidence-based home visiting program — shared best practices happening both in New York and across their national sites.20

Enhanced Communication and Cultural Competency

According to NFP, “When you train staff – you show them how to do the same thing over and over again; but when you educate staff, you teach them critical thinking skills to apply to any situation.” Since no two families are the same, NFP makes the clear distinction that they educate, not train. One mantra they use to educate staff in communication skills is that “the shortest distance between two hearts is a story.” In practice this means that NFP nurses learn how to use motivational interviewing during home visits when they meet a new mother to complete a life history calendar and build trust, learn about the mother’s cultural background, and identify strengths. Questions might include:

- Tell us about a time you were really happy.

- How were you raised?

- What comes to mind when you think of a good mom?

- How did you feel when you found out you were pregnant?

Since women of color are often dismissed when engaging with medical providers, this culturally competent, relationship-building approach creates space for women to feel heard and valued. NFP nurses receive education on cultural humility and health equity, and complete structured modules about cultural awareness within the NFP core education.

Implicit Bias and Racial Affinity Groups

NFP and HFNY both ensure that their staff participate in implicit bias training. Many NFP local network partners provide their own staff trainings as well. For instance, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygienerequires all employees to participate in Race to Justice, an annual training focused on racial equity that also includes implicit bias training. HFNY is considering additional trainings for racial affinity groups where Black, Latina, or white staff meet separately and then come together in a broader group. Racial affinity groups enable Black, Latina, or other people of color to unpack racism, internalized oppression, and pressures of assimilation in a safe space and in the absence of whiteness. Similarly, white people, in their own racial affinity group, can learn more about white privilege and power structures without having to unduly lean on staff of color to educate them on systemic racism. After these trainings, some home visitors shared that in earlier years, they saw their primary role as increasing new mothers’ access to health care. Now they recognize that part of access is about the quality and perceptions of a medical provider. Families are asked to reflect on questions like, “How much are you being listened to by your doctor as the parent of a child?” and “How much are racial biases getting in the way of receiving quality care?” These questions are essential for a home visitor to be the best possible advocate for women of color.

Trauma Informed Care

During interviews, HFNY articulated the need for trauma informed care training, which recognizes trauma symptoms and acknowledges the impact that trauma can have on a person’s life. They want all home visitors to use a conversational approach to learn about each individual family’s strengths, challenges, questions, and interests to gain a better understanding of past experiences and present circumstances. HFA recommends using a curriculum designed to promote social-emotional development, which is crucial for parents who have experienced adverse childhood experiences and who might be having a hard time bonding with their child.21 This approach is particularly important when working with families of color since racial trauma has long-term negative health impacts that must be acknowledged, validated, and supported.22 This framing acknowledges that individuals are not inherently flawed, but rather a product of experiences and exposures that can create unhealthy patterns. Moreover, this approach also acknowledges the strengths that individuals have, rather than just challenges. This is important because explicitly focusing on risks and problems, while omitting protective factors, results in a skewed view of clients that can impact intake and service delivery.23 Many clinicians often omit strength-based questions and adopt a trauma orientation because they have limited time and want to get to the problematic event(s), but it is critical to also understand the factors that contributed to the person’s resilience.

Since racial biases can impact mothers, children, and infants of color, it is essential to not only educate providers on implicit bias, but also to support women with self-advocacy and empowerment skills. This may mean coaching families before a health provider visit, or having an advocate accompany families to meet with medical providers, social service agencies, or employers.

One example comes from New York, where the NFP program was supporting a non-English speaking mother with concerns about her five-week-old infant who vomited after every meal. The mother initially went alone to the emergency department but was dismissed and sent back home. When the bilingual NFP nurse arrived the next day for a home visit, she partnered with the mother to examine the feeding process, formula, and burping technique. She quickly realized that the mother’s intuition was right and accompanied the mother and infant back to the hospital as an advocate and translator, supporting the mother and giving her the confidence to trust her instinct. It turned out that the baby had pyloric stenosis and required emergency surgery.

It is important to note that organizations might have to provide additional staff training to ensure staff have the confidence and skills to effectively serve as advocates. Sometimes paraprofessional home visitors have their own insecurities, including ones about being women of color and worrying about discrimination as well.24 HFNY shared an anecdote about a bilingual Creole-speaking home visitor who said that the hardest part of her job was contacting medical providers who often seemed condescending. Non-credentialed home visitors with lived experiences can bring significant value to families but might need different supports and skill-building than nurse home visitors. Building staff confidence and skills is equally as important as supporting the mother.

There is significant need for diversity in staff and leadership in home visiting programs.25 If home visiting staff are more closely connected culturally, linguistically, racially, or ethnically with the families they serve, they can better help families access programs and resources by translating program registration forms or helping new mothers link up with culturally aligned support systems. Unfortunately, that is often not the case. Only 41 percent of home visitors report having similar traits as most of their clients, related to race, ethnicity, and culture.26

While home visitors and supervisors are diverse in age, they lack gender diversity and are not as racially and ethnically diverse as the families they serve. Nearly all home visitors (99 percent) are women. Increasing the number of male home visitors even by a small percentage can help create role models and help fathers become more positively involved in their children’s development.27 In terms of racial and ethnic diversity, 63 percent of home visitors are white, 13 percent are Black, 16 percent are Latino, and two percent are Asian. Conversely, 23 percent of mothers enrolled in evidence-based home visiting programs are Black and 30 percent are Latino. Nearly half of new mothers of color are assigned a home visitor who does not have a shared racial or ethnic background, according to a 2018 national Home Visitor/Supervisor survey.28, 29 These findings are unfortunately common across states. At New York State’s Department of Health listening sessions mentioned above, mothers shared that they wanted to see more home visiting staff of color. Recommendations were made to increase diversity and scholarships for recruiting home visitors, doulas, and practitioners of color. The need for providers of color is not unique to home visiting and has been starkly reinforced by a recent study showing that mortality rates for Black newborns treated by Black physicians are halved compared with the mortality rates of Black newborns cared for by white physicians.30

Linguistically, there are diversity issues as well. Only 17 percent of home visitors are fluent in Spanish and five percent are fluent in a language other than English. For those staff that can work with non-English speaking parents, additional workload is sometimes placed on them. For example, since forms are usually in English, bilingual home visitors must do double translation to complete necessary data entry. Even if the forms are available in another language, the case notes need to be translated when they are entered into the system. This takes more time and is often not accounted for in caseload assignment or compensation.

Creating a More Diverse Workforce: Lessons from Other Sectors

The need for a more diverse workforce cuts across many human services careers, including the education sector. Many of the strategies for recruiting, hiring, retaining, and promoting a diverse home visiting workforce could be adapted from educational research on recruiting diverse teachers. The following are strategies from a brief on diversifying teacher recruitment by REL Northwest, as applied to the home visiting field:

The need for a more diverse workforce cuts across many human services careers, including the education sector. Many of the strategies for recruiting, hiring, retaining, and promoting a diverse home visiting workforce could be adapted from educational research on recruiting diverse teachers. The following are strategies from a brief on diversifying teacher recruitment by REL Northwest, as applied to the home visiting field:

- Data Use: Use data to forecast home visiting staffing needs, identify underrepresented demographics, and create marketing campaigns to recruit candidates of color.

- Institutional Partnerships: Create partnerships with schools of higher education that attract students of color. NFP, for example, has a partnership with Historically Black Colleges and Universities to support recruitment.

- Relationship-Based Recruitment: Build relationships with students of color before they graduate and before a home visiting job is posted.

- Early Posting: Publish vacancies for home visiting positions well in advance of the start date to create a larger candidate pool that is likely to have more diverse applicants.

- Implicit Bias Education: Educate staff responsible for hiring to recognize their own implicit biases and use interviewing techniques that allow candidates to share their strengths, knowledge, and lived experiences.

- Evaluation Measures: Use multiple measures to evaluate applicant qualifications, including performance-based tasks, such as a mock home visit.

Many low-income families of color disproportionately live in high-stress, high-poverty conditions with limited access to health-related social needs, such as fresh produce, places to exercise, healthy housing, safe neighborhoods, and quality education.31 There is also significant evidence around the impact of early childhood well-being on emotional development later in life.32 The brain produces a biological response when an infant or young child experiences unmet basic needs, a high-stress home environment, or trauma that can result in negative physical and mental health outcomes decades later.33 To truly have a positive, long-term, and holistic impact, home visitors should provide referrals or information to families on existing supports that can address families’ health-related social needs, such as employment, housing, and nutrition — not just maternal health and child development.

Many evidence-based home visiting programs already do this, but not all. To address racial disparities in maternal and child health, home visiting must be integrated into the fabric of a community. Home visitors must be able to facilitate seamless and tailored referrals to additional supports. The COVID-19 pandemic exemplified home visitors’ ability to support families’ needs for diapers, baby wipes, and food. For example, home visiting staff in Rhode Island regularly dropped off supplies to families and ensured that families had food and baby formula, which became scarce at the height of the pandemic. One home visitor left a bag of food on the doorstep of a young family, reporting that the children “cried with joy” because they finally had food they liked.34

One way to use home visiting to address health disparities is to regularly disaggregate services and outcome data by race and ethnicity to identify inequalities. For example, if low birthweight outcomes are improving for white mothers, but not for Black mothers, programs can review their practices and address potential biases or work to reduce structural barriers. It also provides an opportunity to see if mothers and their young children have better health and well-being outcomes when they have home visitors from the same race and ethnicity.

States can focus on disaggregated data to inform their systems work. For example, in 2020 the Vermont Legislature established the Maternal Mortality Review Panel to conduct a comprehensive, multidisciplinary review of maternal deaths in the state for the purposes of identifying factors associated with the deaths and making recommendations for system changes to improve health care services for women.35 The panel will consider health disparities and social determinants of health, including race and ethnicity in maternal death reviews.

In another example, HFA programs in New York use NY State Department of Health data to target high-risk areas throughout the state. They use a matrix of indicators including low birthweight rates, high infant mortality, and elevated maternal fatalities to target services. Because of limited funding resources, the community selection process is competitive. Once they contract with a provider in a particular region, they look at the demographics of the geographic area to ensure they are serving a representative group. For example, if a community is mostly Black, but HFA is serving mostly white mothers, they identify how to better connect with and serve the Black community.

Organizations can also examine their internal policies and processes as well as track internal data to improve how well they serve communities of color. For example, in 2018, HFA created a National Committee on Racial Justice and Cultural Humility to address racial and ethnic disparities. This committee was designed to examine HFA trainings, policies, demographic compositions of governing bodies, and hiring practices. They worked with all affiliate sites to review site materials; communication and language factors; interactions between staff and families; training and training materials; all components of service delivery; and data gathered from various sources (parents, staff, community partners, etc.) through surveys and conversations. These data are then used to develop a plan to address existing and emerging issues.

Additional funding is needed to expand home visiting to more women and families of color. For example, New York’s NFP program only serves six percent of eligible families.36 In addition to reaching more mothers, funds are needed to support best practices in addressing racial equity. The development of implicit bias training, launching of mentorship programs, changing of recruitment strategies, and development of data analytics systems all require additional financial resources. Home visiting must invest in these best practices to improve outcomes for families of color.

There are unprecedented fiscal relief funds from the American Rescue Plan that are currently being deployed to improve the lives of infants and young children as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of these federal funds can be used to address equity issues. A recent summary from ZERO TO THREE, an organization dedicated to ensuring that all babies and toddlers have a strong start in life, outlines how these funding opportunities can address the critical needs of babies and their families.37 Looking specifically at home visiting, the American Rescue Plan provides $150 million in additional funding for Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV). This is in addition to $350 million that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is providing to states to strengthen maternal and child health by expanding home visiting services to families in need, addressing health disparities in infant mortality, and strengthening data reporting on maternal mortality.38

State Medicaid programs are another source of funding for home visiting. A number of states finance home visiting programs with Medicaid funds to help expand capacity, which typically results in more families of color receiving services.39 While Medicaid cannot be used to pay for the full cost of home visiting programs, it can pay for part of the visits and thus reduce unmet need when braided with other federal and state dollars and decrease costly services including lengthy hospital stays. Redressing racial inequities in maternal and childbirth outcomes, in part through home visiting programs, could become more of a priority for state Medicaid programs, which cover on average six in ten births from Black, Latino, and American Indian/Native Alaskan mothers nationwide.40

There is an opportunity to bring a more intentional focus to addressing racial and ethnic disparities to all home visiting programs, regardless of the funding source. MIECHV, for example, has shared a reflection and planning tool on how to infuse cultural and linguistic competency into the recruitment and retention of home visitors but more funding needs to be allocated to support initiatives on the ground.41 Federal funding sources could also include more flexibility to support innovative community-based approaches that have yet to qualify as evidence-based but which show promise to reduce racial and ethnic health disparities.42

Addressing racial and ethnic disparities that lead to health inequities, especially for woman of color, is a critical strategy to break the cycle of injustice and to support the foundational needs of infants and improve their life-long trajectory and outcomes. From prenatal care through early childhood, women and children of color face greater risks and worse pregnancy, delivery, and early childhood outcomes than white women and children. Evidence-based home visiting programs that intentionally use culturally responsive, community driven, and anti-racist approaches and policies can better support families of color and can help reduce high morbidity and mortality rates for women and infants of color. Additional outreach and community engagement efforts —especially among populations and communities most often impacted by racist systems and policies — are needed to incorporate community-led solutions and recommendations gathered from people with lived experiences that can improve home visiting programs and yield better health outcomes and racial equity. The federal resources that have been deployed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic can be used to help address the unmet needs of pregnant women and families with young children in the short-term during this public health emergency. These resources can also be used to significantly move the needle on maternal and child health equity in the long term by focusing intentionally on evolving home visiting practices and policy changes that can redress racial and ethnic disparities.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the following offices for their time and insight given during interviews for this brief. Your commitment to improving home visiting programs to address racial disparities is deeply valued.

New York Office of Children and Family Services (OCFS), Racial Justice and Cultural Humility Home Visiting Workgroup, Healthy Families New York, and New York State Department of Health:

- Claudia Miranda-Julian, Research Scientist, OCFS

- Kristen Kirkland, Research Scientist, OCFS

- Bernadette Johnson, Director, Bureau of Program and Community Development, OCFS (retired)

- Lucinda Caruso, Health Program Administrator 2, New York State Department of Health

- Samantha Cassidy, Health Program Administrator, New York State Department of Health

Nurse Family Partnership:

- Emily Frankel, NE Government Affairs Manager

- Sharon Sprinkle, Eastern Region Consultation Director

- Denise Alba-Rosario, Nurse Consultant

A special note of gratitude to the home visitor and client who allowed us to shadow a virtual session. Witnessing the warmth, trust, connection, and knowledge-sharing between the home visitor and family reinforced the transformative power of this model in improving outcomes for young families. Thank you for opening your home to us.

Endnotes

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention Newsroom. “Racial and Ethnic Disparities Continue in Pregnancy-Related Deaths.” September 2019. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0905-racial-ethnic-disparities-pregnancy-deaths.html.

- M.C. Lu, M. Kotelchuck, N. Halfon, et al. “Closing the Black-White Gap in Birth Outcomes: A Life-course Approach.” Ethn. Dis. 2010. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4443479/.

- C.A. Riddell, S. Harper, J.S. Kaufman. “Trends in Differences in US Mortality Rates Between Black and White Infants.” JAMA Pediatrics. 2017;171(9):911-913. Available at: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/article-abstract/2633490.

- C. Johnson-Staub. “Equity Starts Early: Addressing Racial Inequities in Child Care and Early Education Policy.” CLASP. December 2017. Available at: https://www.clasp.org/publications/report/brief/equity-starts-early-addressing-racial-inequities-child-care-and-early.

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention Newsroom, op. cit.

- J.H. Duffee, A.L. Mendelsohn, A.A. Kuo, L.A. Legano, et al. “Early Childhood Home Visiting.” Pediatrics. Sept. 2017; 140(3):e20172150. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28847981/.

- M. Park, C. Katsiaficas. “Leveraging the Potential of Home Visiting Programs to Serve Immigrant and Dual Language Learner Families.” Migration Policy Institute, August 2019. Available at: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/NCIIP-HomeVisiting-Final.pdf.

- HRSA Maternal and Child Health. “Home Visiting.” Available at: https://mchb.hrsa.gov/maternal-child-health-initiatives/home-visiting-overview.

- Ibid.

- J. Taylor, C. Novoa, K. Hamm, S. Phadke. “Eliminating Racial Disparities in Maternal and Infant Mortality: A Comprehensive Policy Blueprint.” Center for American Progress. May 2019. Available at: https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/women/reports/2019/05/02/469186/eliminating-racial-disparities-maternal-infant-mortality/.

- C. Michalopoulos, K. Faucetta, C.J. Hill, et al. “Impacts on Family Outcomes of Evidence-Based Early Childhood Home Visiting: Results from the Mother and Infant Home Visiting Program Evaluation.” OPRE Report 2019-07. January 2019. Available at: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/mihope_impact_report_final20_508_0.pdf.

- Taylor, C. Novoa, K. Hamm, S. Phadke, op. cit.

- A. Turner, Altarum Institute. “The Business Case for Racial Equity in Michigan.” Prepared by Altarum Institute. May 2015. Available at: https://www.issuelab.org/resources/21951/21951.pdf.

- M. Park, C. Katsiaficas. op. cit.

- Interview on 10/9/2020 with NFP New York staff – Emily Frankel, Sharon Sprinkle, Denise Alba-Rosario.

- Community Voices and Solutions. “Addressing Infant Mortality Among U.S. Born African American Women in Minnesota. Recommendations for Improving Family Home Visiting Programming in Minnesota.” September 2015. Available at: https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/equity/projects/infantmortality/fhvrec.pdf.

- Annie E. Casey Foundation. “Adding a Precision Approach to Culturally Informed Home Visiting.” June 2019. Available at: https://www.aecf.org/blog/adding-a-precision-approach-to-culturally-informed-home-visiting/.

- A. Barlow, B. Mullany, N. Neault, S. Compton, et al. “Effect of a Paraprofessional Home-Visiting Intervention on American Indian Teen Mothers’ and Infants’ Behavioral Risks: A Randomized Controlled Trial.” The American Journal of Psychiatry. Jan. 2013. Available at: https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010121.

- New York City Young Women’s Initiative Working Group. “New York City Young Women’s Initiative Report and Recommendations.” May 2016. Available at: https://www.ggenyc.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/YWI-Report-and-Recommendations.pdf.

- New York State Taskforce. “Maternal Mortality and Disparate Racial Outcomes.” March 2019. Available at: https://www.health.ny.gov/community/adults/women/task_force_maternal_mortality/docs/maternal_mortality_report.pdf.

- Great Kids, Inc. “Healthy Families America.” Available at: https://www.greatkidsinc.org/hfa/.

- M.T. Williams, I.W. Metzger, C. Leins, C. DeLapp. “Assessing Racial Trauma within a DSM-5 framework: The UConn Racial/Ethnic Stress & Trauma Survey.” Practice Innovations. 2018. Available at: https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fpri0000076.

- L. Leitch. “Action steps using ACEs and trauma-informed care: a resilience model.” Health & Justice. April 2017. Available at: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s40352-017-0050-5

- Interview on 8/102020 with NY OCFS Racial Justice and Cultural Humility Home Visiting Workgroup, Healthy Families New York, and NY State Department of Health.

- H. Sandstrom, S. Benatar, R. Peters, D. Genua, et al. “Home Visiting Career Trajectories.” OPRE Report #2020-11. February 2020. Available at: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/101641/home_visiting_career_trajectories_0.pdf.

- Ibid.

- M.E. Gearing, H.E. Peters. H. Sandstrom, C. Heller. “Engaging Low-Income Fathers in Home Visiting: Approaches, Challenges, and Strategies.” Urban Institute. November 2015. Available at: https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/76121/2000538-Engaging-Low-Income-Fathers-in-Home-Visiting-Approaches-Challenges-and-Strategies.pdf.

- Great Kids, Inc. op. cit.

- H. Sandstorm, S. Benatar, R. Peters, D. Genua, et al. op. cit.

- B.N. Greenwood, R.R. Hardeman, L. Huang, A. Sojourner. “Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns.” PNAS. September 2020. 117(35)21194-21200. Available at: https://www.pnas.org/content/117/35/21194.

- S.H. Woolf, P. Braveman. “Where Health Disparities Begin: The Role of Social and Economic Determinants – And Why Current Policies May Make Matters Worse.” Health Affairs. October 2011. Available at: https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0685.

- Executive Office of the President of the United States. “The Economics of Early Childhood Investments.” December 2014. Available at: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/the_economics_of_early_childhood_investments.pdf.

- A. Agorastos, P. Pervanidou, G.P. Chrousos, G Kolaitis. “Early life stress and trauma: developmental neuroendocrine aspects of prolonged stress system dysregulation.” Hormones (Athens). December 2018. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30280316/.

- D. Lewy, R. Yard. The Crucial Role of Home Visiting During COVID-19: Supporting Young Children. Center for Health Care Strategies. June 2020. Available at: https://www.chcs.org/the-crucial-role-of-home-visiting-during-covid-19-supporting-young-children-and-families/.

- An Act relating to the Maternal Morality Review Panel. H.572 (Act 142). July 2020. Available at: https://legislature.vermont.gov/bill/status/2020/H.572.

- Interview on 10/9/2020 with NFP New York staff – Emily Frankel, Sharon Sprinkle, Denise Alba-Rosario.

- ZERO TO THREE. “American Rescue Plan Addresses 5 Critical Needs for Babies.” March 2021. Available at: https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/3921-american-rescue-plan-addresses-5-critical-needs-for-babies.

- HRSA Maternal and Child Health. op. cit.

- K. Johnson. “Medicaid and Home Visiting: The State of States’ Approaches.” Johnson Group Consulting. January 2019. Available at: https://ccf.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Medicaid-and-Home-Visiting.pdf.

- MACPAC Fact Sheet. “Medicaid’s Role in Financing Maternity Care.” January 2020. Available at: https://www.macpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Medicaid%E2%80%99s-Role-in-Financing-Maternity-Care.pdf.

- HRSA Maternal and Child Health. “Infusing Cultural and Linguistic Competence into the Recruitment and Retention of Home Visitors.” November 2017. Available at: https://mchb.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/mchb/MaternalChildHealthInitiatives/HomeVisiting/clc-workforce-development.pdf.

- M. Park, C. Katsiaficas. op. cit.