As the Pay for Success movement has grown throughout the United States, a broad array of intermediaries, service providers, and prospective investors have set their sights on state Medicaid programs, which serve one in five Americans, as among the most bankable beneficiaries of any number of social impact investments.2 For example, Medicaid, a federal-state partnership that provides publicly financed health insurance for low-income individuals and people with disabilities, pays a considerable price for hospitalizations that could be avoided through more effective primary and preventive care, and by addressing the social determinants of health. Accordingly, Medicaid meets one of the key criteria for vetting potential Pay for Success end payers — namely, savings that can be monetized through social impact interventions.

However, despite all the enthusiasm directed at Medicaid from the outside, state Medicaid leaders have been slow to embrace Pay for Success — perhaps even painfully slow, depending on one’s vantage point. Whereas dozens of inquiries and feasibility studies have been pursued, only the state of South Carolina has closed a Pay for Success transaction that directly leverages Medicaid funds — and not exactly in a true end-payer capacity. The reasons for this slow take-up are many. First, the Pay for Success field arguably needs to do a better job of articulating the unique value that Pay for Success could provide to Medicaid programs. Second, the opportunity cost associated with devoting time and resources to Pay for Success implementation must be reduced. Below are suggestions for a two-pronged strategy to increase Pay for Success’ traction in Medicaid, specifically: 1) honing the Medicaid-specific value proposition; and 2) addressing key limitations that are otherwise likely to remain barriers to Medicaid engagement in the near term.

Refining the Value Proposition: What Can Pay for Success Help Medicaid “Get Done Better?”

Fortunately, there are numerous ways that Pay for Success offers Medicaid a valuable and potentially “better-than-other-alternatives” strategy for achieving key policy objectives. Specifically, Pay for Success may provide Medicaid with an opportunity to:

Onboard investments in social determinants of health. There is growing recognition across the health care sector that social determinants play a key role in driving health outcomes and associated health care costs. Although the United States spends up to 95 percent of health care dollars on direct medical services, roughly 50 percent of preventable deaths are attributable to nonmedical indicators, including social circumstances, environmental factors, and individual behaviors.3 Given this heightened appreciation for nonmedical factors, Medicaid programs are actively designing and implementing strategies to address beneficiaries’ social determinants of health. These strategies include two primary pathways: 1) exploring options to use Medicaid funds more flexibly to pay for nonmedical services; and 2) implementing new payment incentives for providers to attend to social determinants directly.

With each of these pathways, Medicaid agencies and their contracted partners are in the early stages of a new journey — navigating new landscapes of services and service providers beyond the familiar realm of traditional health care delivery. And understandably, many are proceeding with caution as they look to address multiple new lines of inquiry, such as assessing unmet community needs, identifying evidence-based strategies to address these needs, untangling webs of existing relationships and funding streams, identifying well-positioned partners, and, ultimately, negotiating business arrangements that satisfy mutual operational and financial needs.

In short, this is a new and heavy lift for the health care sector, and one where Pay for Success may have a valuable role to play in easing the onboarding process. In this context, Pay for Success could be viewed as a temporary financing strategy to mitigate various risks associated with navigating new terrain. Specifically, by enabling Medicaid payers or providers to pay only “if it works,” and by putting tightly defined parameters around populations to be served, timeframes for implementation, and outcomes to be rewarded, Pay for Success can provide structured supports that minimize the risk and extent of stumbles and dead-ends along the way.

Scale evidence-based prevention strategies. Medicaid programs and the partners they contract with are responsible for managing the health of large populations over broad geographic regions. As an entitlement program, Medicaid is often constrained in what it can offer on a limited geographic basis, given federal requirements to offer most covered services statewide to all who could benefit. Meanwhile, in many cases, effective models of social service delivery are far more localized — specific to neighborhoods or individual communities — and not necessarily available at the capacity to adequately serve all Medicaid enrollees in a region or state.

In this context, Pay for Success may serve as a valuable financing strategy to help scale up such models to achieve the reach necessary to meet Medicaid needs. Whereas traditional models of service payment generally do not address ramp-up costs, particularly on the low margins where most social service providers operate, Pay for Success gives providers upfront access to capital, thereby supporting geographic expansion, hiring and training of new staff, and other necessary capital investments. Accordingly, Pay for Success can provide a win-win for both Medicaid stakeholders and social service providers — meeting demands of scale for Medicaid while addressing the financial and operational constraints on growth for the service providers.

Maintain clear boundaries on Medicaid-covered services. In the context of growing interest in social determinants, Medicaid has been facing new questions regarding the most cost-effective use of program funds. For example, given all the evidence around the favorable impacts of supportive housing on health care costs, there is growing interest across states to cover housing and related services for certain high-risk subsets of Medicaid enrollees.4 However, there are also considerable countervailing pressures related to maintaining Medicaid’s integrity and focus as a health insurance program, and not exposing U.S. taxpayers to an ever-broadening mandate (and associated bill) for what Medicaid could and should cover.

Pay for Success provides one mechanism that can help Medicaid achieve its goals of addressing key social determinants of health while maintaining its established boundaries as a health insurance program. Specifically, Pay for Success enables Medicaid to pay for desired health outcomes without having to amend federal coverage limitations on the underlying services that generate those outcomes. In this way, Pay for Success is similar to other allowable mechanisms that could afford Medicaid greater flexibility to use its dollars beyond the scope of the approved Medicaid benefit. Two of the other mechanisms that are gaining a lot of current attention include “in lieu of” and “value-added” services. As defined in federal regulations, in lieu of services allow states to contract with managed care plans to provide non-covered benefits, so long as they are demonstrated to be cost-effective alternatives; value-added services enable managed care plan investments in a broad array of activities that improve health care quality. With both of these mechanisms, Medicaid programs can broaden the array of services that Medicaid managed care plans can use their funds to purchase. However, whereas each of these pathways expressly expands the universe of services that Medicaid pays for, Pay for Success arguably enables the same outcomes without risking the potential creep in program scope. By enumerating the outcomes to be paid for (as opposed to the nonmedical services from which they originate) Medicaid may, through Pay for Success, have a greater chance at maintaining program integrity and avoiding risk or perception of runaway entitlements, as compared with these other mechanisms.

Address broader societal preference for health care over social service investment. Despite concerns at federal and state levels regarding ever-rising health care costs and their growing share of government budgets through Medicare, Medicaid, and other public coverage programs, the United States as a society continues to show a strong preference toward investing taxpayer dollars in health care, as compared with other social services. As Elizabeth Bradley and her colleagues at Yale University demonstrated, for every dollar the United States spends on health care, it spends 90 cents on social services, whereas our industrialized peers spend two dollars.5 Notably, Bradley’s findings also highlight the poorer health outcomes associated with the under-allocation of resources to social services relative to health care services. And, whereas the current policy and political climate could well lead to reductions in government health care spending, it is not likely that we will see any of these funds diverted to social service funding.

Given this uniquely American preference to spend money on health care at the expense of other social services, Pay for Success may provide one mechanism for diverting some of those health care dollars back into the social service sector. While the funds may come through the public budgeting process as health care monies, Pay for Success can allow policymakers to reroute a portion of those funds toward otherwise underfunded social services, to the extent that those services can drive desired improvements in health outcomes. To that end, Pay for Success may be an antidote to the U.S. obsession with health care — a tool to get closer to that 2:1 ratio of social service to health care spending that has been proven to drive better health outcomes.6

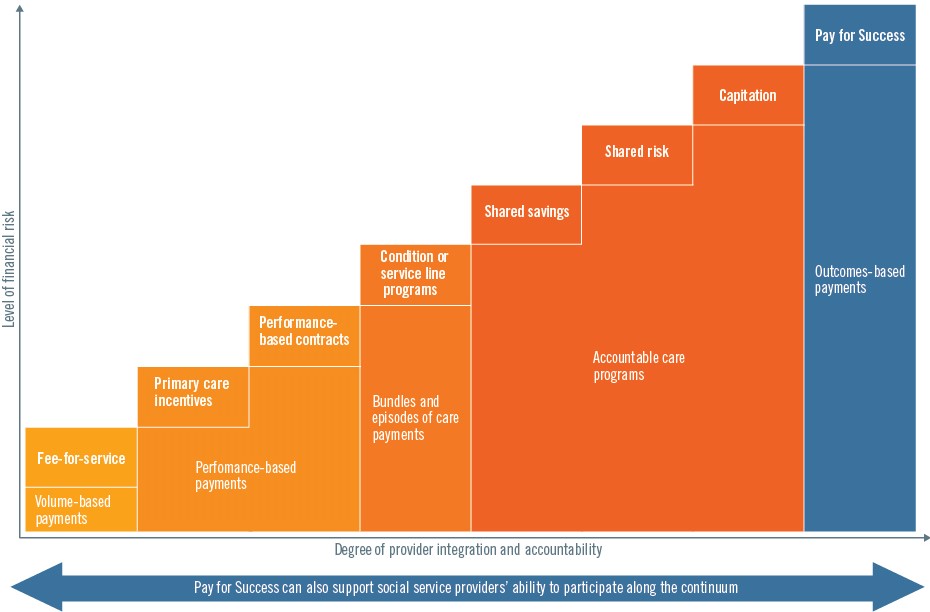

Support the health care system’s broader evolution toward paying for value. Increasingly, a dominant area of focus for Medicaid and other payers is in transitioning the health care payment system from one that rewards volume to one that rewards value. Historically, health care providers have been reimbursed on a fee-for-service basis — creating substantial incentives to increase visits and procedures, and few disincentives for unnecessary, duplicative, or potentially harmful medical care. While better known for its coverage provisions, the Affordable Care Act included a number of initiatives to stimulate broad-scale change in provider payment. Largely driven by the newly created Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation, value-based payment models have begun to proliferate, with lofty targets across payers for moving payments to value-based arrangements over the next three to five years. These arrangements generally fall along a continuum of fee-for-service plus bonuses tied to quality performance, shared savings/risk, and global payments, whereby providers manage the total cost of care for a defined population or suite of services, subject to quality performance benchmarks (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Performance Benchmark Continuum

On the one hand, Pay for Success could be viewed as an onboarding strategy for social service providers to enter into value-based payment arrangements. To date, the more advanced value-based payment arrangements — such as those including shared risk or capitation — have generally been taken on by large health care systems that are well capitalized and have the administrative infrastructure to manage that risk. By leveraging private investment, Pay for Success provides a mechanism for less-well-capitalized service providers to avoid that risk, enabling a broader universe of providers to participate in advanced payment arrangements without fears of destabilizing a fragile social service sector. On the other hand, beyond bringing in new providers, Pay for Success can also push the envelope of how Medicaid and other health care payers think about value-based payments. While the current continuum of value-based payment arrangements presents an important shift away from fee-for-service, it arguably falls short of what Pay for Success considers outcomes-based payment. Although current value-based payment efforts better connect health care payment incentives with quality of care and hold providers accountable for managing costs, they arguably have not yet envisioned a future where providers are explicitly paid to produce, maintain, or improve health — not just as a bonus on top of fee-for-service or as a condition for retaining profits under global budgets, but as the basis of the payment system itself. In this sense, Pay for Success or outcomes-based payment could be construed as a future state along the value-based payment continuum, or as a modified trajectory away from a focus on managing total costs to managing the production of desired outcomes. These concepts are highly related, but they have different points of emphasis that are worth noting. In this context, Pay for Success — and particularly the most recent efforts to develop rate cards that establish a fee schedule for specific outcomes — could provide important new tools for Medicaid as it and other payers further hone their approach to value-based payments over time.

Identify new financial resources in a constrained budgetary environment. Pending the outcomes of ongoing debates about the Affordable Care Act, it is possible that Medicaid could undergo significant changes in the years ahead — potentially away from its status as an open-ended entitlement program and toward some form of capped federal funding commitment through block grants or other related mechanisms. Given the commensurate interest among congressional leaders in reducing federal spending, there is considerable likelihood that any structural changes to the Medicaid program could be accompanied by federal funding cuts. For example, the Affordable Care Act and Medicaid reform bill put forth in early 2017 by Republican leadership included an $880 billion cut to federal Medicaid spending over ten years.7

With the prospect of fewer Medicaid resources and stronger demands on the safety net associated with losses in health care coverage, states would face new pressures to do more with less. Whereas Pay for Success might otherwise have been viewed as a modest source of discretionary capital to seed pilot projects, a new policy picture could place more of a premium on Pay for Success’ ability to supplement limited public funds with private investment capital, as well as to provide a glide path for Medicaid to move over time toward paying only for what works.

What it Will Take to Gain Traction in Medicaid

As described above, Pay for Success could represent a valuable tool for Medicaid in a variety of ways. However, to gain traction, some key limitations need to be addressed:

Scale. Medicaid programs are large; for example, the median-sized program (Virginia) covers approximately one million people with a budget of more than $8 billion. Accordingly, to capture the attention and imagination of Medicaid leadership, Pay for Success needs to move beyond small, local pilots and deliver a measurable impact on cost and quality outcomes at scale. Otherwise, the requisite investment of staff time and other resources will have a hard time stacking up against other higher-priority, higher-impact initiatives.

Replicability. Medicaid leadership will want to know going into a Pay for Success transaction that, if successful, it will be straightforward to replicate the model in other regions of the state or for other targeted outcomes. Continued efforts to minimize the administrative burden associated with Pay for Success transaction structuring will be key to assuring Medicaid of the potential for replication.

State-level return on investment (ROI). Among other benefits, most states view Pay for Success as an opportunity to generate state-level Medicaid savings. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services does not currently allow states to commit the federal portion of savings achieved through Pay for Success initiatives for repayment of investor capital. Simply put, this means that unless federal policy changes, Pay for Success transactions with Medicaid agencies as end payers need to have sufficient ROI that the state portion of savings alone (which is half or less, depending on the state) is sufficient to repay investors. For certain populations, such as individuals dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid, this state share of any savings is even less.

Willingness to partner with Medicaid managed care. Many Pay for Success enthusiasts see it as a mechanism to fundamentally change the way government spends its money and are reluctant to consider the private sector as an end-payer. However, given that more than 60 percent of Medicaid enrollees receive their benefits through managed care plans, many states view their health plan partners as the entities best poised to enter into Pay for Success arrangements. The ROI equation is generally easier for the plans as well, given that the plans do not have to distinguish between state and federal dollars, and have greater flexibility to commit their combined Medicaid funds as they see fit. Given that plans are increasingly being held accountable for delivering outcomes, Pay for Success may present an attractive transaction structure for them, guaranteeing that their financial outlays are tied to outcomes that they are increasingly expected to deliver.

Alignment with the language of value-based payments. To date, Pay for Success has not adequately aligned itself with broader health care trends around value-based payments. To be embraced by Medicaid, Pay for Success needs a clearer narrative on how it relates to other efforts to transform health care payment practices — both in terms of where it fits in and what it is uniquely poised to contribute. The more Pay for Success can relate to Medicaid in terms that Medicaid understands, the easier it will be for Medicaid stakeholders to understand how and where it could be useful.

Fit within existing policy parameters. As described earlier, one clear value of Pay for Success to Medicaid is the flexibility it may provide to fund activities that are otherwise difficult for states to cover under traditional Medicaid rules. Thus, to the extent that implementing Pay for Success requires policy changes or other time-intensive administrative actions, states may prefer to devote that energy to removing the underlying barriers to the flexibility they are seeking. In other words, if Pay for Success as a “workaround” is laborious to implement, states may be better off trying to address the more fundamental policy barriers themselves.

Looking Ahead

With all the large-scale changes Medicaid could be facing in the months ahead, stakeholders looking to engage Medicaid in new ideas need to closely align their pitches with the program’s most pressing priorities. Fortunately, there are numerous ways in which Pay for Success can help states deliver on core strategic objectives: Transforming payment systems to reward value and addressing social determinants of health, to name two. The greater the alignment in language, the ease of execution, and the potential for scale, the more likely Pay for Success will find a ripe audience among Medicaid leaders.

1 Nancy Lions, “The Disruptive Start-Up: Clayton Christensen On How to Compete with the Best,” Inc. Magazine (February 1, 2002), available at http://www.inc.com/magazine/20020201/23854.html.

2 Kaiser Family Foundation, “Medicaid Pocket Primer” (January 3, 2017), available at http://kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaid-pocket-primer/.

3 J. Michael McGinnis, Pamela Williams-Russo, and James Knickman, “The Case for More Active Policy Attention to Health Promotion,” Health Affairs 21 (2) (2002): 78–93; Paula Braveman and Laura Gottlieb, “The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes,” Public Health Reports 129 (Supplement 2) (2014): 19–31, available at http://www.publichealthreports.org/issueopen.cfm?articleID=3078.

4 For example: Laura Sadowski et al., “Effect of a Housing and Case Management Program on Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalizations Among Chronically Ill Homeless Adults: A Randomized Trial,” JAMA 301(17) (2009): 1771–1778.

5 Elizabeth Bradley et al., “Health and Social Services Expenditures: Associations with Health Outcomes,” Quality and Safety 20 (10) (2011), available at http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/content/20/10/826.

6 Ibid.

7 Congressional Budget Office, “Cost Estimate: American Health Care Act” (March 13, 2017), available at https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/costestimate/americanhealthcareact.pdf.