Program Snapshot

Name: Community Care of Brooklyn (Maimonides Medical Center)

Goal: Engage people in their communities to more effectively identify local challenges and take actions to reduce the impacts of social determinants of health.

Featured Services: Community engagement approach called participatory action research used to find ways to prevent cardiovascular disease in a high-risk urban environment.

Target Population: Adults, with complex health and social needs, at risk for cardiovascular disease.

With about 2.7 million residents, Brooklyn would be the third-largest city in the United States if it were not a borough of New York City. As in many big cities, the quality of Brooklyn residents’ health often depends on which neighborhood they call home. Many parts of Central Brooklyn have high levels of concentrated poverty, poor housing and environment, residential segregation by race, sizable immigrant populations, low educational attainment, inadequate job opportunities, and limited access to healthy foods and preventive care. These factors, fueled by continuing systemic racial, economic, and social inequities, contribute to health disparities that result in higher rates of chronic disease and mortality for Central Brooklyn residents than for more advantaged New Yorkers living in majority-white neighborhoods.

While there is a growing consensus that social determinants of health — such as poverty, inadequate housing, school quality, and community resources — play a significant role in health outcomes, there is still much to be learned about how to advance that understanding into action. To explore this issue, Community Care of Brooklyn (CCB), the largest network of coordinated care for Brooklyn’s Medicaid population, decided to invest in a research model that engages with, and takes its direction from, community residents. The approach was chosen to enable collective action for finding effective ways to prevent cardiovascular disease in Central Brooklyn.

Operating under New York State’s Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) program, CCB, a Performing Provider System (PPS) with Maimonides Medical Center as its fiduciary, is a consortium of hospitals, federally qualified health centers, more than 850 organizations, and about 4,600 clinical providers. DSRIP, an initiative that draws on over six billion dollars of federal and state funding, aims to improve health for New York Medicaid patients and, by 2020, to reduce their preventable hospital admissions and emergency department use by 25 percent. DSRIP supports 25 PPS collaborations like CCB across the state. Of these, 10 PPSs are in New York City, with CCB being the largest in Brooklyn, with an attribution of over 600,000 patients.

COMPLEX CARE INNOVATION IN ACTION

This profile is part of an ongoing series from CHCS exploring strategies for enhancing care for individuals with complex health and social needs within a diverse range of delivery system, payment, and geographic environments. LEARN MORE »

Using Participatory Action Research to Identify Community Needs

CCB decided early on in its existence to focus on cardiovascular disease due to its high incidence rate and deaths attributed to it in Central Brooklyn. However, before developing a set of interventions around this issue, CCB was interested in learning more about how, where and why patients struggled with it. Instead of relying on standard investigatory methods, CCB turned to a community engagement approach called participatory action research (PAR).

The PAR process elicits from communities the solutions they think would have the most impact on issues they are confronting and gives them an equitable role in identifying local priorities. Using PAR practices to develop and implement the cardiovascular health study meant involving Brooklyn residents and stakeholders in the project from the start, to find out their priorities for creating better health locally. Students, who were also Brooklyn residents, or attended school within the catchment areas, conducted the surveys, making the PAR method beneficial as an educational and skills-building endeavor as well as for finding solutions to improve community health.

“In meeting with our community-based organization partners, our health care partners, and advocates for those organizations, we decided that the best thing we could do is take our direction from the community, rather than impose what we thought was the solution for them. We did not want a top-down approach,” says CCB’s chief executive officer, David I. Cohen, MD, MSc. “The communities already understand what the gaps are in services, what they would like to see addressed,” Dr. Cohen says. “That was a better way to go.”

As first steps, representatives from more than 40 local organizations met to help shape the proposed study, according to Okenfe Lebarty, CCB’s senior community engagement specialist. “We asked, ‘How do we make this project include the voices of all the community members?’” he says. Another session involved elected officials from the neighborhoods that would be included. As the project took shape, local residents helped create the questions that would be asked in the research survey. “Having those community voices and participation in every aspect of planning has really been great,” says Lebarty. “It shows you the importance that community members and advocates place in the project.”

Building a Team

“We decided that the best thing we could do is take our direction from the community, rather than impose what we thought was the solution for them. We did not want a top-down approach.”

CCB’s first PAR project, conducted in the summer of 2016, focused on two Central Brooklyn neighborhoods with high rates of cardiovascular disease, Brownsville and East New York. The study, known as PAR I, surveyed residents to better understand how they assessed their own health, and drew upon their first-hand insights to identify community resources. Residents also recommended actions that could improve neighborhood health challenges.

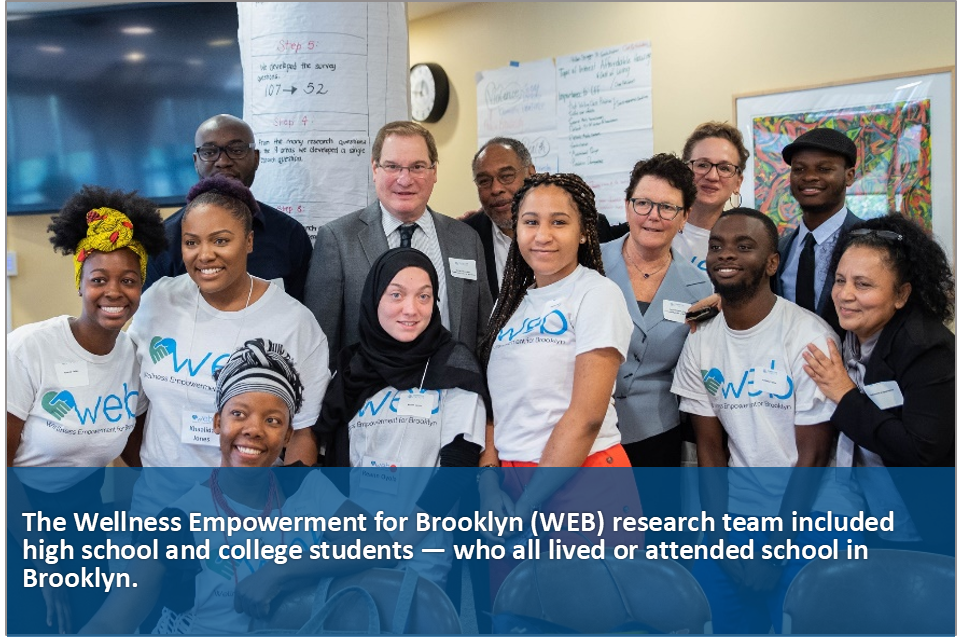

CCB partnered on the project with the DuBois-Bunche Center for Public Policy at Medgar Evers College of the City University of New York, MIT, and NextShift Collaborative, LLC, a team of consultants headed by J. Phillip Thompson, PhD (he later became New York City’s deputy mayor for strategic policy initiatives in 2018). The project hired 28 high school and college students — who all lived or attended school in Brooklyn — to be part of the research team, which was collectively called Wellness Empowerment for Brooklyn (WEB).

The students were supervised by graduate researchers from MIT and Pratt Institute, and conducted on-the-street surveys with 525 residents of the two neighborhoods. They were trained in how to approach people, how to explain what the research was about, and how to conduct in-person interviews. Carrying surveys in their backpacks, the student researchers went out in small groups to talk with people they met in public spaces, such as parks, recreation centers, senior housing, or at neighborhood events. They did not do door-to-door interviewing because of concerns for students’ safety. Interviews lasted about 20 minutes. All respondents lived in local zip codes.

Brooklyn resident Khaalida Jones, who recently graduated from Medgar Evers College, was a student researcher on the project and part of the WEB research team. Jones says she was drawn to the PAR method because “I could connect with community members in a way that we don’t typically do in an urban environment.” At times, the people she interviewed were so interested in the project that they volunteered to participate later in a community focus group.

Survey questions asked about physical, mental, social, environmental and financial factors that affect cardiovascular health risk. After completing the 50-question survey, respondents could add any concerns they felt needed to be covered but had not been asked. Student researchers also took photographs of healthy and unhealthy features in the neighborhood environment and gathered feedback from residents about where they felt safe or unsafe, healthy or unhealthy, in their community. The students then mapped that information.

“A lot of people were forthcoming with their personal stories,” Jones says. “Their narratives were a major part of the qualitative aspect of the research.”

Survey Results

PAR 1 findings reflected community-wide problems that affect health. More than one-third of respondents considered the local environmental health “poor” or “very poor.” About 40 percent were “unsure” or “very unsure” of what their income would be in the next month. More than half were not able to eat nutritious meals at least one day per week and one-fourth said it happened on most days or every day. Half did not have affordable quality produce nearby.

“A lot came up that was surprising to me,” says Karen Nelson, MD, MPH, chief medical officer of CCB. “There was more food instability than I expected, and more of a food desert in these dense urban neighborhoods than people understand.”

As for positives, among others, the study found that many residents thought highly of neighborhood social and cultural assets. Eight recommendations emerged (see sidebar on page 4), which were subsequently recommended for funding by a CCB subcommittee of community leaders and other stakeholders.

Among these recommendations were suggestions to: (1) create urban farm gardens on school campuses, hospital property, and vacant land; (2) add more community health workers to better connect residents with services;

(3) collaborate with local organizations on summer camps focused on exercise and healthy eating; and (4) increase jobs in construction, green energy, and health care. Of these, CCB prioritized food justice to improve health, and participated in a citywide food program established with the mayor’s office to support access to healthy food, as well as funded a hydroponic farm in a middle school. Year-round physical activity programs are underway in two local schools. “We are developing a lot of the recommendations,” Lebarty says.

Participatory Action Research Study Recommendations

The PAR I team reported eight recommendations to a CCB subcommittee, the Workgroup on Cardiovascular Disease in the Community:

- Transform the local food system by expanding urban farming.

- Work with New York City to develop business plans for local farms.

- Build on city efforts to organize and support local bodegas seeking to offer fresh produce.

- Study the feasibility of establishing a “community wellness hub.”

- Expand the presence of community health workers.

- Develop summer camp programs focused on nutrition and exercise.

- Reduce violence by expanding economic opportunities through education, apprenticeships and job placement.

- Launch a Healthy Buildings program to tackle residential conditions that exacerbate asthma.

The PAR II project made recommendations for improving local challenges that influence residents’ health:

- Invest in equitable developments. Promote housing affordability to maintain racial and economic diversity, especially for low-income residents.

- Partner with local institutions and small businesses to create jobs and increase income for long-time residents.

- Restructure Central Brooklyn health care system to make hospitals economic and community anchors, building better hospital-community relationships.

- Create collaborations between health care systems, philanthropies, policy makers, and community-based organizations to address challenges and build local organizing capacity.

In addition, the PAR 1 research findings informed Vital Brooklyn, a $1.4 billion state initiative to improve community health in Central Brooklyn. Based on some of the insights gained from PAR I, Vital Brooklyn intends to bring new health care facilities, more affordable housing, and other resources to the area.

“Prior to this kind of effort, engagement of the community was a matter of (conducting) a community needs assessment to identify what the community needed and then imposing a set of programs that were defined by health care facilities as what people should do,” says Dr. Cohen. “You can talk all you want about nutrition and exercise, but if there are no safe spaces (for physical activity) and no place that sells the kind of food that’s needed, then it wasn’t particularly successful.”

Building Trust

“[One interviewee] said there have been many occasions where people came into the neighborhood, harvested information, and nothing was done. He felt that people come in and take, but never give back. The emotion behind that response stuck out to me.”

One of the most memorable encounters student researcher Jones had while conducting PAR I interviews happened with a man who wanted nothing to do with the study. “He said there have been many occasions where people came into the neighborhood, harvested information, and nothing was done. He felt that people come in and take, but never give back,” she recalls. “I was taken aback by that. The emotion behind that response really stuck out to me.”

She spoke about the man and his reaction when the research team held debriefing sessions. “We decided, as a group, that it was important for us to maintain a level of consistency in the neighborhood — that was the only way we were going to build trust,” says Jones. The group decided to have a social media presence and share all findings with the community. “We made a commitment to be consistent and not have the residents look at us with skepticism the way they looked at previous studies,” she says.

There was, of course, another difference between the PAR study and previous research: the students doing the interviewing were from the neighborhood, or from one nearby. Jones lives in Crown Heights, a Central Brooklyn community she describes as having many Caribbean American residents, herself included, as well as other groups. After PAR I, she signed up to be a student researcher for the next study, PAR II, which was conducted in Crown Heights, Bedford Stuyvesant, and East Flatbush in the summer of 2017. She says that being a local helped.

“Canvassing my neighborhood, I saw a lot of familiar faces and was able to break through some of the negative attitudes toward our presence,” she says. Residents who knew her would tell others that she was okay to speak with, and they encouraged their neighbors to take the survey. “Especially in communities with high immigrant populations, they don’t know what this information is going to be used for,” Jones says. “If people don’t know you, they’re not going to open up with you.”

Engaging for Action

The community-based research has revealed that even though Central Brooklyn neighborhoods may be contiguous, they have different challenges and priorities for overall health improvement. Compared to respondents in the PAR I neighborhoods (Brownsville and East New York), those interviewed in PAR II (Crown Heights, Bedford Stuyvesant, and East Flatbush) said the greatest problems facing health in their communities were: (1) gentrification and housing affordability; (2) the need for economic development; (3) a lack of neighborhood leadership and cohesion; and (4) for hospital leaders and workers to connect better with local communities.

CCB and The New York Community Trust funded PAR II. Other sponsors were Interfaith Medical Center, Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center, and the CCB Community Action and Advocacy Workgroup. The research team included graduate researchers from MIT, Pratt Institute, and the University of California, Berkeley, with interviews conducted by more than three dozen local college and high school students. The student researchers surveyed 1,000 residents in two-and-a-half weeks.

CCB and The New York Community Trust funded PAR II. Other sponsors were Interfaith Medical Center, Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center, and the CCB Community Action and Advocacy Workgroup. The research team included graduate researchers from MIT, Pratt Institute, and the University of California, Berkeley, with interviews conducted by more than three dozen local college and high school students. The student researchers surveyed 1,000 residents in two-and-a-half weeks.

Suggestions for change, from community members and stakeholders, included making investments in equitable and affordable housing, forming partnerships between local institutions and small businesses to increase jobs and wealth, and having Central Brooklyn hospitals become economic and community anchors. Discussions are continuing on how to implement the findings.

In summer 2018, similar community-based research, PAR III, was conducted in the Canarsie, Flatbush, and Flatlands neighborhoods. For PAR III, CCB partnered with MIT, Medgar Evers College, Brooklyn College and Kingsborough Community College. A PAR IV study is underway.

With each iteration of the study, participatory action research has shown the value of involving local residents equitably with institutions and researchers, to find solutions for health challenges. “Folks tend to lump issues together and communities together, in a one-size-fits-all approach to all of them,” Lebarty says. “With PAR, people are beginning to realize that communities may be similar in issues but the way those are affecting them is quite different.”

About the Center for Health Care Strategies

The Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) is a nonprofit policy center dedicated to improving the health of low-income Americans. It works with state and federal agencies, health plans, providers, and community-based organizations to develop innovative programs that better serve people with complex and high-cost health care needs. To learn more, visit www.chcs.org.

About the Complex Care Innovation Lab

Maimonides Medical Center is part of the Complex Care Innovation Lab (CCIL), a national initiative led by CHCS through support from Kaiser Permanente Community Health and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Since 2013, CCIL has brought together leading innovators from across the country who are focused on improving care and outcomes for low-income individuals with complex medical and social needs. For more information, visit www.chcs.org/innovation-lab/.

Author Robin Warshaw is an award-winning writer who focuses on medicine, social issues, and health care.