Program Snapshot

Name: TakeCCARE (Complex Care Assisting and Reviewing Education)

Goal: Identify barriers to care for low-income patients living with complex medical and social needs and connect them with community resources.

Featured Services: Uses Geographic Information Systems software to identify areas where people lack access to health and social support services, and deploy outreach workers to those areas to conduct home visits and coordinate care needs.

Target Population: Uninsured VCU Complex Care Clinic patients in East Richmond with two or more inpatient hospitalizations and/or multiple emergency department (ED) visits within a three-month period.

In late September 2016, Briana Ricks, an outreach worker employed by Virginia Commonwealth University Health System’s (VCU Health) Complex Care Clinic (CCC) in Richmond, met with a new patient who had been admitted to the hospital for the fifth time that month. Struggling with diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension, and a history of substance use, the woman was being hospitalized frequently due to fluid build-up in her lungs.

Ricks arranged to visit the patient in her home and gained her trust, learning that sometimes she skipped her dialysis treatments and when she did go, often left before the dialysis was complete. Ricks, a recent graduate from VCU who majored in health education, made weekly visits with the patient. “On some days when she had dialysis, I’d sit with her for the three hours to make sure she didn’t get antsy and I’d try to observe what issues were causing her to skip treatment,” says Ricks. It turned out that keeping the patient company and using home visits to talk through how important it was to complete dialysis had an enormous impact. “My patient went from being hospitalized four to five times a month to staying out of the hospital for six straight months,” says Ricks. “It was really worth it.”

COMPLEX CARE INNOVATION IN ACTION

This profile is part of an ongoing series from CHCS exploring strategies for enhancing care for individuals with complex health and social needs within a diverse range of delivery system, payment, and geographic environments. LEARN MORE »

Program Background

This hands-on approach to addressing the complicated social determinants of health impacting high-need, high-cost patients is at the heart of TakeCCARE (Complex Care Assisting and Reviewing Education), a pilot program underway at VCU Health. As one of six demonstration sites under the Center for Health Care Strategies’ Transforming Complex Care initiative, VCU Health’s TakeCCARE pilot is deploying outreach workers to serve as the bridge between the health system and the community. Made possible with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF), Transforming Complex Care is aimed at refining and spreading effective care models that address the complex medical and social needs of high-need, high-cost patients.

“My patient went from being hospitalized four to five times a month to staying out [of the hospital] for six straight months. It was really worth it.”

As the largest safety-net hospital in Virginia, VCU Health cares for more than 165,000 patients annually. The health system runs the CCC, which to date has served more than 1,000 uninsured patients with complex medical and social needs who live at or below 100 percent of the federal poverty level and meet any of the following criteria:

- Five or more chronic illnesses;

- Under age 50 and diagnosed with diabetes and complications;

- Referral from a community primary care provider; or

- Utilization patterns indicative of complex needs, such as two or more inpatient hospitalizations or six or more emergency department (ED) visits over a three-month period.

Opened in 2011, the CCC uses a team-based approach that includes primary care physicians, nurses, case managers, social workers, outreach workers, a psychologist, and a pharmacist. The team strives to improve the quality of care and decrease the costs associated with the sickest patients, who often have financial, social, and other barriers to accessing care. The CCC model of care has had a substantial impact on both improving the quality of care for high-need, high-cost patients and reducing utilization of avoidable and costly services like ED visits and inpatient hospitalizations. Based on an internal analysis conducted as a part of the Transforming Complex Care evaluation, VCU estimates that in its first year, patients served by the clinic achieved a 44 percent decline in inpatient admissions, a 38 percent decrease in ED visits, and a 49 percent reduction in total hospital costs compared to similar patients not engaged by the clinic.

Yet despite these positive outcomes, there were indications that a segment of CCC patients needed even more help managing their health. This was apparent in data showing that hospital readmission rates had failed to budge, and in fact rose from 25 percent in FY2013 to 27 percent in FY2015. The consensus was that some portion of CCC patients were dealing with persistently unmet social needs — including food and housing insecurity, financial distress, low health literacy, and transportation barriers — that could not be met by the clinic team alone. In addition, these patients often missed appointments and were cycling in and out of the hospital too frequently.

That is where VCU Health’s pilot program comes in. The TakeCCARE pilot uses a data-informed approach to identify eligible high-need patients and dedicates two outreach workers to build trusting relationships with these patients. This high-touch model includes visiting patients in their homes and connecting them to medical and social services.

“There are a lot of reasons why people come to hospitals,” says Jennifer Ohashi, interim director of health data analytics at VCU Health. “It’s really about getting to the root of the problem for all these different patients. It’s been tremendous having the outreach workers trying to figure out what the issues are, because without that we can’t really affect outcomes.”

Mapping the Need Geographically

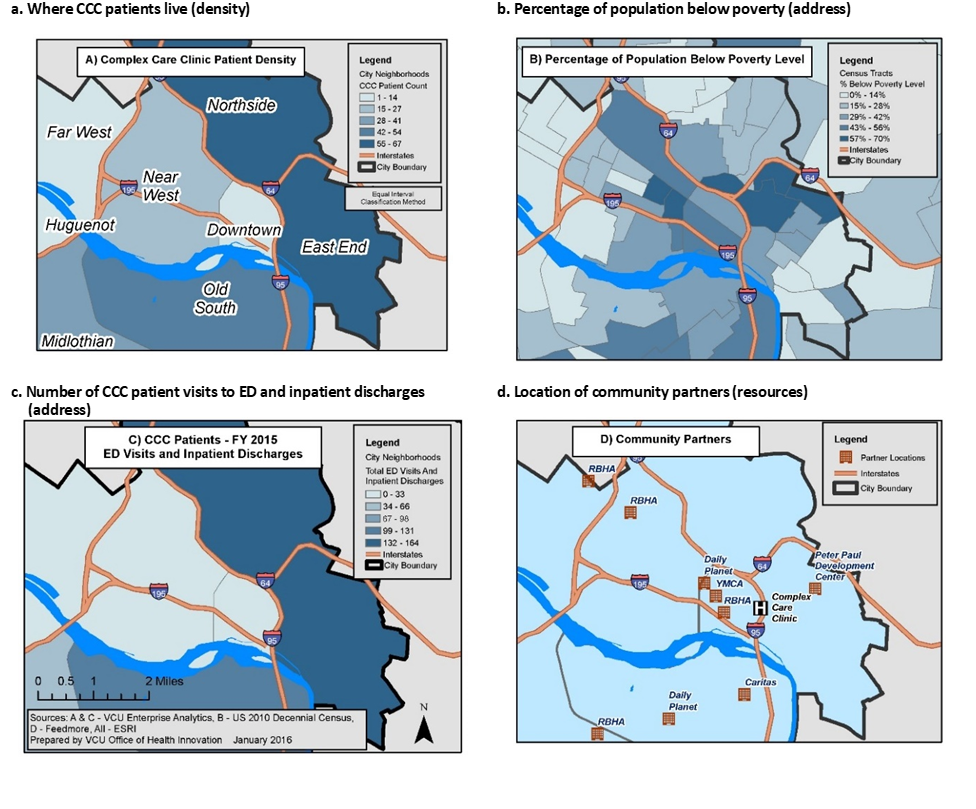

Before the pilot could begin, a team from the University’s Office of Health Innovation used Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping techniques known as “hotspotting” and “coldspotting” to identify regions of the service area within Richmond where the intervention was most needed. The team created four individual maps, then overlaid them to find the highest-need population and to locate nearby resources for services. The GIS mapping includes: (a) where CCC patients live; (b) percentage of population below poverty; (c) number of CCC patient visits to ED and inpatient discharges; and (d) location of community partners.

Defining “Hotspotting” and “Coldspotting”

- Hotspotting – Identifying where the majority of patients with complex health and social needs live.

- Coldspotting – Identifying areas where patients’ needs are not being met, often because there are few social service providers”

Using census and other demographic data, the team found that the East End of Richmond was disproportionately impacted by poverty, had a high-uninsured rate, and higher inpatient and ED utilization and higher costs in comparison to the rest of the city (largely concentrated in four public housing communities). However, the neighborhood also had several key resources, including a food bank, a YMCA with an established diabetes self-management program, housing assistance, and a community agency offering mental health services. With funding from RWJF, the CCC was able to hire Briana Ricks and Kswanna Letsinger as full-time outreach workers to engage patients outside the clinic and connect them to these vital programs.

“Often that medical condition is not the only thing the patient is dealing with. They may have a mental health issue, a problem managing their medication, or social barriers are present that keep them from successfully managing their health.”

The TakeCCAre pilot, which began in August 2016, includes patients who are identified after being flagged in the CCC, either by clinic staff or in weekly data reports, as having had multiple hospitalizations and/or multiple ED visits within three months. “All of the patients have multiple chronic conditions that are most likely not being managed very well,” says Kim Lewis, Community Outreach Manager for VCU Health. These include diabetes, hypertension, COPD, HIV, and renal failure. “Often that medical condition is not the only thing the patient is dealing with,” says Lewis. “They may have a mental health issue, or are having a problem managing their medication, or other social barriers are present that keep them from successfully managing their health.” Patients are excluded from participating if they have an active substance use disorder, have committed a violent crime, or pose a safety risk for the outreach workers.

Identifying Patient-Level Needs

Ricks and Letsinger typically meet their patients for the first time at the hospital. If the patient agrees to participate in the pilot, a follow-up visit takes place within two weeks after discharge at the patient’s home. The data analytics team has created three detailed surveys that the outreach workers use to collect a range of information about a person’s basic demographics, details of what takes place at each encounter, and finally, a social needs assessment for each patient at baseline, six weeks, and 12 weeks. The outreach workers also help determine whether patients are eligible for Medicaid, Medicare, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or other social services if not already enrolled.

During a home or hospital visit, the outreach worker determines if the patient has unmet social needs, asking about caregiving for a child or adult in the home, education, employment, food insecurity, health literacy, housing, language barriers, or transportation. “So if a patient says, ‘I need help buying food this week,’ we want to know on the survey if this need was addressed,” says Ohashi. “Did the outreach worker provide a referral to a food bank or provide anything else for this patient for that one particular need. Our surveys are very need-focused,” she adds.

Despite the pilot’s robust data collection component, Ohashi says the data only tell part of the story. “I knew from my own experience that data are just not enough — these are real people with really intricate problems.” With an eye to the value of patient stories, the patient encounter form includes a notes section where the outreach workers can add a narrative of what happened at a home visit that is reviewed by their supervisor.

“A lot of times people don’t necessarily want to tell the whole truth to their doctors and nurses. They’re ashamed or afraid of being judged, and of course our patients are really very sick. Patients think, ‘This outreach worker is willing to meet with me in my home, in my comfort zone, they must really care about me and I can open up to them.’”

Outreach workers also complete weekly audio entries, called “Reflection Logs,” detailing what worked well that week, what the rest of the team could have done to be more helpful, or what might be done better next time. This is where, for example, the outreach workers can describe a patient who was giving money to her boyfriend instead of buying medication, or can explain that a patient does not mean to be “noncompliant,” she is just frustrated that heart failure has made it impossible for her to work, pay her bills, and take care of herself. Patient stories hold clues to what interventions — a free bus pass, a radio to make dialysis less boring, job training — can actually help people to better manage their health.

The Value of Strong Personal Relationships

“A lot of times people don’t necessarily want to tell the whole truth to their doctors and nurses,” says Ricks. She and the other outreach workers have bachelors’ degrees and some background in health education, but no clinical training. “Our patients are often ashamed or afraid of being judged, and of course they are really very sick,” she says. The outreach workers approach their patients outside the clinic; they are “just regular people” meeting patients in their communities and homes. “Patients think, this person is willing to meet with me in my home, in my comfort zone, they must really care about me and I can open up to them,” Ricks adds.

This easy rapport allows the outreach workers to deeply impact many of their patients’ lives. One of Letsinger’s current patients has uncontrolled diabetes, asthma, and hypertension among other conditions. As they got to know each other, he felt comfortable asking her questions and revealed that he did not understand how his diet, lack of exercise, and other behaviors were hurting his health. He was surprised to learn that hypertension and high blood pressure — terms used interchangeably by the clinical team — were the same thing.

This easy rapport allows the outreach workers to deeply impact many of their patients’ lives. One of Letsinger’s current patients has uncontrolled diabetes, asthma, and hypertension among other conditions. As they got to know each other, he felt comfortable asking her questions and revealed that he did not understand how his diet, lack of exercise, and other behaviors were hurting his health. He was surprised to learn that hypertension and high blood pressure — terms used interchangeably by the clinical team — were the same thing.

Letsinger worked with her patient to educate him about his health; they talked about nutrition and she helped him sign up for diabetes education classes and an exercise program at the nearby YMCA (a partner program). They created a menu together, and Letsinger taught him how to read the ingredients on food labels. “He’s been adding salads to his dinner 4-5 times a week and going to the YMCA for classes,” says Letsinger. “I’ve worked with him for just a month and he’s already lost 10 pounds just by changing his diet.”

Early Lessons

Although utilization and cost outcomes are still being analyzed, early takeaways are emerging from the VCU TakeCCARE pilot. While the pilot’s goal is to reduce hospital readmissions, the researchers found early on that they were limiting their reach by requiring that the first interaction be with a patient who had been admitted to the hospital. “There are people who interact with the clinic who could very much benefit from the services we provide, but were not necessarily admitted to the hospital recently,” says Ohashi. Now, the program has adjusted its eligibility to include patients who come to the ED two or more times and are placed on “observational status” and not admitted. They have also begun including patients in the pilot who were admitted over a weekend when an outreach worker did not get a chance to interact with them.

Another lesson is that a 12-week intervention may not be long enough for some patients. VCU Health’s original program design specified that outreach workers would perform weekly home visits for a minimum of six weeks up to a maximum of 12 weeks, or until the patient is able to self-manage as measured by patient activation scores. “One of our early learning points is that sometimes it takes four to five weeks just to get a person comfortable enough to talk with the outreach worker,” says Lewis. For the purposes of the pilot, the 12-week endpoint “graduation” is still officially in place. However, for the patients with the most complex social needs, particularly those who lack basic resources like secure housing or food, the outreach workers continue beyond that endpoint, making home visits and connecting patients to resources.

Lewis is convinced that VCU Health’s pilot is sustainable in the long term, and that the program’s leadership will be able to make the case that outreach workers interacting with patients with complex medical and social needs outside of the clinic or hospital can lower readmission rates. Outreach workers have been working with uninsured patients at VCU Health for 15 years already. “We’re already in the business of outreach workers,” says Lewis. “The data we get will sweeten the pot in terms of the impact that home visits have in helping high-need, high-cost patients manage their care.”

Author Naomi Freundlich is a journalist with more than 25 years of experience writing about health care.

About the Center for Health Care Strategies

The Center for Health Care Strategies (CHCS) is a nonprofit policy center dedicated to improving the health of low-income Americans. It works with state and federal agencies, health plans, providers, and community-based organizations to develop innovative programs that better serve people with complex and high-cost health care needs. To learn more, visit www.chcs.org.

About Transforming Complex Care

AccessHealth Spartanburg is part of Transforming Complex Care, a multi-site demonstration aimed at refining and spreading effective care models that address the complex medical and social needs of high-need, high-cost patients. This national initiative, made possible with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and led by CHCS, is working with six organizations to enhance existing complex care programs within a diverse range of delivery system, payment, and geographic environments. For more information, visit www.chcs.org/transforming-complex-care.